The Nationals have no shortage of story-lines unrelated to ADHD, including a joyous All-Star ace who dominates in Chicken Mode with curveballs and slip-and-falls, the most talked-about pitcher who won’t pitch in the postseason, theleast talked-about pitcher who will pitch in the postseason, a rock at third base who’s savoring his first chance at a championship since Little League, a shark roaming center field, a Beast who needs neither bat nor ball to hit a grand slam, and bullpen readings of Fifty Shades of Grey. Heck, even the Nats’ broadcasters are compelling: Color commentator F.P. Santangelo visits Abner Doubleday’s grave, follows closer Drew Storen’s mom’s Twitter feed, and can still barehand a foul popup from the press box.

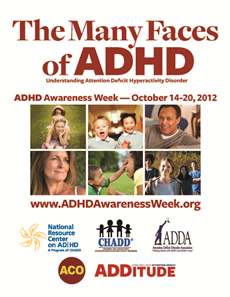

Amidst this fabulously entertaining season, the Washington Nationals are quiet but compelling evidence of a fundamental sea-change in how people talk about, think about, and manage adult ADHD.

The Accidental Poster-Child of ADHD

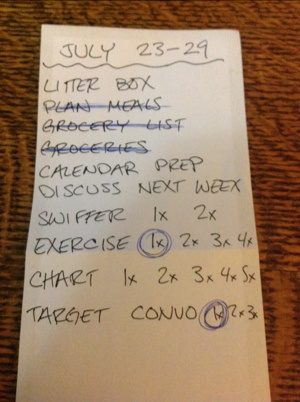

The Nationals sparked interest on the ADHD front heading into the 2011 season when they signed Adam “Cool” LaRoche, the veteran first baseman with thesweet swing, snappy glove, and the most publicly diagnosed brain in the major leagues. Around the same time, the Nationals signed Tom Gorzelanny, a left-handed pitcher who is also open about having ADHD but whose diagnosis received far less public scrutiny than LaRoche.

Then again, perhaps no one’s ADHD diagnosis has received as much publicity as LaRoche, the son and brother of professional ballplayers who made his own major league debut with the Atlanta Braves in 2004.

Before Andres Torres became Gigante, before Shane Victorino and the “Own It”project, Adam LaRoche was a talented young Atlanta Brave who ”unlocked” on a routine defensive play in May 2006, leading to 4 unearned runs and anointing LaRoche the accidental poster-child of ADHD in professional sports.

Take nothing away from the courage of Scott Eyre, who in 2001 became the first major league ballplayer to publicly admit having ADHD (Eyre, a left-handed reliever, played 13 years in the majors with the Giants, Cubs, White Sox, Blue Jays, and Phillies). But Eyre’s announcement some 5 years prior did not prevent the popular derision that rained down on LaRoche when his diagnosis became public in 2006.

LaRoche has handled the public examination of his personal challenge withgrace and courage, urging people – especially children – not to be ashamed about asking for help. He’s brought the same poise to the ballpark in 2012, providing consistently excellent offense and defense that has carried the Nationals through a remarkable spate of injuries that threatened to derail their season. Tomorrow, October 7, 2012, after years of bad teams, bad luck, and bad injuries, LaRoche will be back in the playoffs for the first time since that fateful mental mistake in 2006, batting cleanup for the top-seeded team in the National League.

The Rookie Who’s No Accident

As if LaRoche’s tale of quiet vindication wasn’t enough, I started playing around with a post on the Washington Nationals in mid-June, when teen phenom Bryce Harper matter-of-factly explained how he’d felt sitting on the bench for the first time in his brief major-league career, then scoring the winning run as a pinch-hitter in the top of the ninth inning:

“I don’t like sitting. I have really bad ADD, so I’m always off the wall, and just crazy when I sit . . . . [In] spring training this past year, sitting down and really trying to learn the game while . . . sitting really helped me out here.”

– Bryce Harper, MASN post-game interview, Fenway Park, June 10, 2012

That wasn’t the first time the rookie had publicly described having ADHD, and it probably won’t be the last. Sure, he’s only 19, but Harper has spent plenty of time in the spotlight, simultaneously heralded as the next Ruth / Mays / Mantle / Junior / insert-all-time-great-ballplayer-here while somehowexceeding all expectations. He’s an attention magnet with a flair for the dramaticand un/intentionally hilarious.

But for all the attention paid to Harper’s every word and deed, his occasional mentions of having ADHD seem to prompt, at most, a shrug.

It’s no big deal.

Harper, like any ballplayer, makes the occasional mistake – not often, but occasionally – and when he does, it’s not blamed on ADHD; reporters don’t call up experts who’ve never met him to opine on how ADHD is affecting his batting average or his personal life; no one speculates on whether he’s taking medication or gaining some unfair advantage; there aren’t insinuations that he might not “really” have ADHD.

Instead, as the rookie leads the Washington Nationals’ first-ever charge into the postseason, we wait with breathless anticipation to see what Harper will do next.

It Is a Big Deal

Compare today’s collective blink to the scorn LaRoche faced 6 years ago. For Harper’s ADHD to be no big deal is, in itself, a very big deal.

It’s a big deal to hear ADHD treated as simply a challenge to be addressed, rather than a shameful secret or a punchline.

It’s a big deal to learn that having ADHD doesn’t give the world a free pass to delve into the most personal quirks of your brain.

It’s a big deal to see people with ADHD excel on the same playing field as everyone else by cultivating other abilities to overcome this disability.

It’s a big deal to know that people with ADHD can reap the benefits of well-directed hard work.

So, to Adam LaRoche, and Bryce Harper, and Tom Gorzelanny, and everyone else who wakes up every day facing ADHD along with life’s other challenges – thank you for the inspiration, keep up the good work, and LET’S GO NATS.

Small wonder, then, that I was so drawn to Barbara Kingsolver’s heroine in

Small wonder, then, that I was so drawn to Barbara Kingsolver’s heroine in  Any biological child of mine is more likely to have ADHD. It is not a certainty, but it is a probability (as wanting children makes it more probable, but not certain, that I will have children).

Any biological child of mine is more likely to have ADHD. It is not a certainty, but it is a probability (as wanting children makes it more probable, but not certain, that I will have children).

Certified by: CRPO and CCPA. Fully insured and supervised practise. Fees covered by most extended health plans.

Certified by: CRPO and CCPA. Fully insured and supervised practise. Fees covered by most extended health plans.