I really like the Jungian way of looking at things. I loved going to the Jungian groups in Halifax every Tuesday evening and watching films and then discussing the concepts. The compiled works of Carl Jung were the first psychology books I ever read I believe.

Rory

********

Source: Shadow Self and Carl Jung: The Ultimate Guide to the Human Dark Side | HighExistence

How well do you know yourself?

If you’re like most people, you probably have a decent idea about your own desires, values, beliefs, and opinions.

You have a personal code that you choose to follow that dictates whether you are being a “good” person.

If there is any one thing you can know in this universe, surely it is who you are.

But what if you’re wrong?

What if much of what you have come to believe about yourself, your morality, and what drives you is not an accurate reflection of who you truly are?

Now, before you launch into a, “Hey, you don’t know me, you don’t know my life, you don’t know what I’ve been through!”-style defense, ponder this for a second:

Have you ever said or done something really shitty, mostly on an impulse, that you later regretted?

After the damage was done and the other person involved was hurt, you couldn’t bury your shame fast enough. “Why did I say that?” you might have asked yourself in frustration.

It’s that “Why?” question that indicates the presence of a blind spot. And though the reason for your reaction may have been obvious (perhaps even “justified”), the lack of control you had over yourself betrays the existence of a different person lurking beneath your carefully constructed idea of who you are.

If this person is coming into focus for you, congratulations—you’ve just met your shadow self.

The Shadow: A Formal Introduction

“The shadow is a moral problem that challenges the whole ego-personality, for no one can become conscious of the shadow without considerable moral effort. To become conscious of it involves recognizing the dark aspects of the personality as present and real. This act is the essential condition for any kind of self-knowledge.”

— Carl Jung, Aion (1951)

The “shadow” is a concept first coined by Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung that describes those aspects of the personality that we choose to reject and repress. For one reason or another, we all have parts of ourselves that we don’t like—or that we think society won’t like—so we push those parts down into our unconscious psyches. It is this collection of repressed aspects of our identity that Jung referred to as our shadow self.

If you’re one of those people who generally loves who they are, you might be wondering whether this is true of you. “I don’t reject myself,” you might be thinking. “I love everything about me.”

However, the problem is that you’re not necessarily aware of those parts of your personality that you reject. According to Jung’s theory, we distance ourselves psychologically from those behaviors, emotions, and thoughts that we find dangerous.

Rather than confront something that we don’t like, our mind pretends it does not exist. Aggressive impulses, taboo mental images, shameful experiences, immoral urges, fears, irrational wishes, unacceptable sexual desires—these are a few examples of shadow aspects, things people contain but do not admit to themselves that they contain. Here are a few examples of common shadow behaviors:

1. A tendency to harshly judge others, especially if that judgment comes on an impulse.

You may have caught yourself doing this once or twice when you pointed out to a friend how “ridiculous” someone else’s outfit looked. Deep down, you would hate to be singled out this way, so doing it to another reassures you that you’re smart enough not to take the same risks as the other person.

2. Pointing out one’s own insecurities as flaws in another.

The internet is notorious for hosting this. Scan any comments section and you’ll find an abundance of trolls calling the author and other commenters “stupid,” “moron,” “idiot,” “untalented,” “brainwashed,” and so on. Ironically, internet trolls are some of the most insecure people of all.

3. A quick temper with people in subordinate positions of power.

I caught this one all the time when I worked as a cashier, and it is the bane of all customer service employees. People are quick to cop an attitude with people who don’t have the power to fight back. Exercising power over another is the shadow’s way of compensating for one’s own feelings of helplessness in the face of greater force.

4. Frequently playing the “victim” of every situation.

Rather than admit wrongdoing, people go to amazing lengths to paint themselves as the poor, innocent bystander who never has to take responsibility.

5. A willingness to step on others to achieve one’s own ends.

People often celebrate their own greatness without acknowledging times that they may have cheated others to get to their success. You can see this happen on the micro level as people vie for position in checkout lines and cut each other off in traffic. On the macro level, corporations rig policy in their favor to gain tax cuts at the expense of the lower classes.

6. Unacknowledged biases and prejudices.

People form assumptions about others based on their appearance all the time—in fact, it’s a pretty natural (and often useful—e.g. noticing signs of a dangerous person) thing to do. However, we can easily take this too far, veering into toxic prejudice. But with so much social pressure to eradicate prejudice, people often find it easier to “pretend” that they’re not racist/homophobic/xenophobic/sexist, etc., than to do the deep work it would take to override or offset particularly destructive stereotypes they may be harboring.

7. A messiah complex.

Some people think they’re so “enlightened” that they can do no wrong. They construe everything they do as an effort to “save” others—to help them “see the light,” so to speak. This is actually an example of spiritual bypassing, yet another manifestation of the shadow self.

Projection: Seeing Our Darkness in Others

“If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?”

― Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Seeing the shadow within ourselves is extremely difficult, so it’s rarely done—but we’re really good at seeing undesirable shadow traits in others. Truth be told, we revel in it. We love calling out unsightly qualities in others—in fact, the entire celebrity gossip industry is built on this fundamental human tendency.

Seeing in others what we won’t admit also lies within is what Jung calls “projection.” Although our conscious minds are avoiding our own flaws, they still want to deal with them on a deeper level, so we magnify those flaws in others. First we reject, then we project.

One way that we all experience this dichotomy of rejection and projection, for example, is when we have a hard time admitting that we’re wrong.

When I was seven, I had the grand idea that my younger brother and I would run away. Nothing was particularly unpleasant in our home lives at the time; when my brother asked why we were running away, I simply shrugged and said, “Because all the kids do it.”

We packed our blue Sesame Street suitcase with all the essentials: cookies, toys, and juice boxes. After taking the screen down from our first-story bedroom window, we tossed the suitcase onto the ground below. I urged my brother to jump out first and, with complete trust in me, he did. As he crouched behind the thorny hedge just beneath the window, I swung my leg outside and sat poised between the safety of my bedroom and the open air of the outside world.

I looked at the cars driving by, suddenly aware of the boundary I was about to cross. On one side of the window I was safe; my mom knew where I was and I was doing everything she expected me to. On the other side of the window, however, rules were being broken. If she knew that we were going outside without her knowledge, our mom would surely kill us.

This moment of panic inspired in me a sudden need to retreat into the safety zone. I called down to my brother, telling him that I had forgotten something and would be right back—instead I hurried to tell my mom that he was running away. She scrambled outside, where she found him in the bushes, still waiting for me. The look of betrayal contorted his features as he gaped at me, and I parried with a self-righteous stare. He was grounded, while I became his “savior.”

While it’s easy to see my behavior as simply that of a shitty, mean sister (which, trust me, I have assured myself repeatedly that I was being), there was actually an entire invisible psychological process happening beneath the surface. As soon as I realized that my brother and I were doing something that wasn’t the fun and brazen endeavor I imagined and would actually land us in a massive heap of trouble, I had to devise a way to protect myself from the consequences.

My seven-year-old “big sister” ego identity wouldn’t permit me to admit that I was wrong—such an act would put my social status into question for me (and more importantly, my subservient little brother). Instead, I projected the wrongness onto my brother and ran to tell my mom. I suspect that my unconscious mind wanted to see the consequences of that wrongness played out in order to learn the lesson of how to avoid the trouble in the future… I just maybe didn’t want to experience those consequences for myself.

By projecting the deviant behavior onto my poor little brother (whom, I assure you, I spoil to death in our older age as penance), I avoided having to confront the dangerous behavior in myself. And this is something that, in our own ways, we all do.

In this case, being in the wrong was the thing I rejected in myself. Most people hate admitting when they’re wrong because doing so is accompanied by the uncomfortable emotions of embarrassment, guilt, and shame. Rather than confront the possibility of being wrong, therefore, people often go to extreme lengths to prove to themselves and others that they are right—even if it means hurting someone else.

Unfortunately, our impulse to avoid the unpleasant confrontation with the truth is so strong that we remain completely unaware of what’s happening. The mind ignores and buries all evidence of our shortcomings to protect itself—i.e. to prevent the experience of pain—storing it deep within our unconscious minds. This doesn’t make those thoughts, memories, and emotions go away, but it does put them somewhere we don’t have to “see” them.

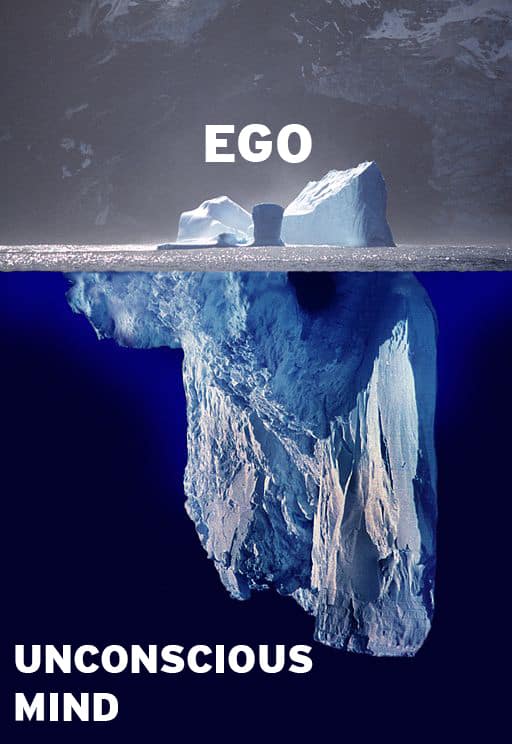

Our conscious minds are where our ego personality dwells—the “I” that walks around every day talking to other people. When you think of who “you” are, this is the part of yourself you usually identify with.

However, that “you” is only the part of your identity that is visible to you. Your conscious awareness is like a light enabling you to observe what is happening inside your mind.

Beneath that conscious “light” is a whole world of “darkness” containing those very aspects of ourselves that we have strived to ignore. The ego is only the tip of the iceberg floating above the sea, but the unconscious mind is the vast mountain of ice lurking beneath the surface.

(Source)

Much of that bulk consists of our repressed thoughts, memories, emotions, impulses, traits, and actions. Jung envisioned those rejected pieces coming together to form a large, unseen piece of our personality beneath our awareness, secretly controlling much of what we say, believe, and do.

This secret piece of the personality is the shadow self.

Origins of the Shadow Self

Our society teaches us that certain behaviors, emotional patterns, sexual desires, lifestyle choices, etc. are inappropriate. These “inappropriate” qualities are usually those that disrupt the flow of a functioning society—even if that disruption means challenging people to accept things that make them uncomfortable. Anyone who is too challenging becomes outcast, and everyone else moves on.

Now, we humans are highly social creatures, and the last thing we want is to be excommunicated from the rest of our tribe. So, in order to avoid being cast out, we do whatever it takes to fit in. Early in our childhood development, we find where the line between what is socially “acceptable” and “unacceptable” is, and we spend the rest of our lives trying to toe it.

When we cross that line, as we all frequently do, we suffer the pain of society’s backlash. People judge us, condemn us, gossip about us, and the unpleasant emotions that come with this experience can quickly become overwhelming. However, we don’t actually need people to observe our deviances to suffer for them. Eventually, we internalize society’s backlash so deeply that we inflict it on ourselves.

The only way to escape from this perpetual recurring pain is to mask it. Enter the ego. We tell ourselves stories about who we are, who we are not, and what we would never do to protect ourselves from suffering the consequences of being an outcast. Ultimately, we believe these stories, and once we develop a firm belief about something, we unconsciously discard any information that contradicts that belief. In the world of psychology, this is known as confirmation bias: humans tend to interpret and ignore information in ways that confirm what they already believe.

The problem is that literally everyone possesses qualities that society has deemed undesirable. People fall short of others’ expectations, have a temper flare-up, are excessively gassy, etc. The ideal individual in any society is one who lives up to impossible standards.

What no one wants to admit to others is that we are all secretly failing to meet those standards. Women wear makeup, men use Axe deodorant, advertisers Photoshop celebrities, people filter their personalities with photos and status updates on social media—all to mask perceived flaws and project an image of “perfection.” Jung called these social masks we all wear our “personas.”

“Unfortunately there can be no doubt that man is, on the whole, less good than he imagines himself or wants to be. Everyone carries a shadow, and the less it is embodied in the individual’s conscious life, the blacker and denser it is. If an inferiority is conscious, one always has a chance to correct it. Furthermore, it is constantly in contact with other interests, so that it is continually subjected to modifications. But if it is repressed and isolated from consciousness, it never gets corrected.”

— Carl Jung, Psychology and Religion (1938)

Uncommon thoughts and emotions put us at an even higher risk of being alienated from society. Ideas that are challenging or contrary to social norms are considered dangerous and are best left unexpressed if one wishes to “fit in.”

Emotionally, any mood other than happy, or at least neutral, is considered undesirable. Rather than admit we are going through a difficult experience, thus making others uncomfortable with the knowledge that we are uncomfortable, we say that we’re fine when we’re really not.

Ironically, this need to avoid things that make us and others uncomfortable undermines our ability to confront and either heal or integrate them. And if this failure to heal is bad for us as individuals, the effects of that failure on a mass scale are catastrophic.

When our cultures were in their infancies, past humans beheld their more animalistic tendencies (murder, rape, war, etc.) with revulsion and fear. They developed a moral code, most often based on religious beliefs, about how the ideal, or “enlightened,” human should behave.

While these ideals were intended to be inspiring, giving humans a model for spiritual growth, they were challenging in their tendencies to go against fundamental aspects of human nature. In many ways this is a good thing, since a society that allows rape, murder, and rampant violence does not tend to be a very good one to live in.

However, our collective moral codes fall short because they only offer ideals. Religious and secular morals only tell us who to be, not how to become that person. When solutions are offered, they are bogged down in esoteric practice that the average person has a hard time understanding—at least not without years of mentoring and study, something that not all of us have the luxury to undergo. We can’t all be monks, after all.

The result is that we struggle to change in ways that require us to suppress our base animal instincts without giving them safe outlets through which to manifest. In other words, we push our failures into the unconscious, where we can ignore them and go on pretending to be the people society wants us to be. We get to pretend to be enlightened without actually doing the deep inner work that it takes to move through the developmental process.

Enlightenment: The Shadow Formula

“Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.”

— Carl Jung

Jung’s proposed solution to this schism is for the individual to undergo “shadow work.” What we repress never stays repressed, it lives on in the unconscious—and, despite what our egos would have us believe, the unconscious mind is the one really running the show.

“Filling the conscious mind with ideal conceptions is a characteristic of Western theosophy, but not the confrontation with the shadow self and the world of darkness. One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious.”

— Carl Jung, “The Philosophical Tree,” Alchemical Studies (1945)

Shadow work, then, is the process of making the unconscious conscious. In doing so, we gain awareness of our unconscious impulses and can then choose whether and how to act on them. We begin this process when we take a step back from our normal patterns of behavior and observe what is happening within us. Meditation is a great way to develop this ability to step back from ourselves, with the goal being to gain the ability to do this as we go about our daily lives.

The next step is to question. When we observe ourselves reacting to psychological triggers, or events that prompt an instant and uncontrolled reaction from us, we must learn to pause and ask ourselves, “Why am I reacting this way?” This teaches us to backtrack through our emotions to our memories, which hold the origins of our emotional programming.

Identifying triggers can be a difficult process due to our natural desire to avoid acknowledging the shadow self. Our tendency is to justify our actions after the fact, when really the best thing we can do is avoid acting reactively or unconsciously in the first place. Cultivating an awareness of the shadow is the first step to identifying our triggers—but before we can do that, we must first overcome our instinctive fear of our shadows.

Perhaps the biggest issue people face when confronted with the shadow is the question, “Am I a bad person?” Acknowledging the shadow means acknowledging that we contain darkness, a capacity for malevolence. As Jung wrote in Psychology of the Unconscious:

“It is a frightening thought that man also has a shadow side to him, consisting not just of little weaknesses and foibles, but of a positively demonic dynamism. The individual seldom knows anything of this; to him, as an individual, it is incredible that he should ever in any circumstances go beyond himself. But let these harmless creatures form a mass, and there emerges a raging monster; and each individual is only one tiny cell in the monster’s body, so that for better or worse he must accompany it on its bloody rampages and even assist it to the utmost. Having a dark suspicion of these grim possibilities, man turns a blind eye to the shadow-side of human nature.”

Jung indicates that under certain circumstances, all human beings have the capacity to do horrible, brutal things. And somewhat paradoxically, familiarizing ourselves with these dark potentialities and accepting them as part of us is perhaps the best way to ensure that they are never actualized. But again, it’s profoundly difficult to do this, particularly because we desperately don’t want to think of ourselves as “bad” people.

So, do taboo thoughts, hurtful actions, and the capacity to commit atrocities make you a bad person? No, not necessarily. Of course, everyone has a different definition of how “good” and “bad” people act—and those moral definitions are to some extent irreducibly subjective and arbitrary—but when it comes to the general consensus of “goodness,” you can make mistakes and hurt others without having an awareness of what you’re doing and still be a good person. Beyond that, once you acknowledge the massive potential for both light and darkness within each human being, the dichotomy of “good” people vs “bad” people begins to seem reductive and misleading. Above all, you’re human, and as such, too complex to be neatly categorized.

Nonetheless, the idea of being a good person is not without merit, and most of us intuitively understand that it’s a fine idea to move in the direction of greater self-awareness, self-mastery, and compassion. Doing difficult shadow work—recognizing and correcting our unconscious destructive patterns—is a crucial aspect of becoming a better person.

Once we identify the original sources of our psychological triggers (e.g. repressed fear, pain, aggression, etc.), only then can we begin to heal and integrate those wounded parts of ourselves. Integration, in Jung’s definition, means that we cease rejecting parts of our personalities and find ways to bring them forward into our everyday lives. We accept our shadows and seek to unlock the wisdom they contain. Fear becomes an opportunity for courage. Pain is a catalyst for strength and resilience. Aggression is transmuted into warrior-like passion. This wisdom informs our actions, our decisions, and our interactions with others. We understand how others feel and respond to them with compassion, knowing that they are being triggered themselves.

One aspect of integrating the shadow self is healing our psychological wounds from early childhood and beyond. As we embark on this work, we begin to understand that much of our shadow is the result of being hurt and trying to protect ourselves from re-experiencing that hurt. We can accept what happened to us, acknowledge that we did not deserve the hurt and that these things were not our fault, and reclaim those lost pieces to move back into wholeness. (For especially deep traumas, it is advised to work with a trained psychologist on these issues.) This is a very intensive and involved process and merits another separate article to cover, but those who wish to know more can find a myriad of information on the subject in books, videos, articles, and self-improvement groups.

Unfortunately, many philosophies insist that people can become enlightened without doing this deep inner work. The proposed solution within these philosophies seems to be to actively ignore unconscious impulses rather than to dig in and understand them.

Not trying to point fingers, but many of these philosophies come from Newer (*cough, cough*, Age) ideas, which often misinterpret ancient teachings to fit into the modern desire for convenience and comfort. I’d love to rip these teachings a new one in another article, but for now, it is good to be wary of anyone who insists that you can reach enlightenment without working on those parts of yourself that are messy and painful. Ultimately, you’ll have to use your own discretion to decide what resonates most with you—but don’t be surprised to find yourself facing a crisis if you opt to take the path of avoidance.

As Jung points out, we can’t correct undesirable behaviors until we deal with them head on. The shadow self acts out like a disobedient child until all aspects of the personality are acknowledged and integrated. Whereas many spiritual philosophies often denounce the shadow as something to be overcome and transcended, Jung insists that the true aim is not to defeat the shadow self, but to incorporate it with the rest of the personality. It is only through this merging that true wholeness can be attained, and when it is, that is enlightenment.

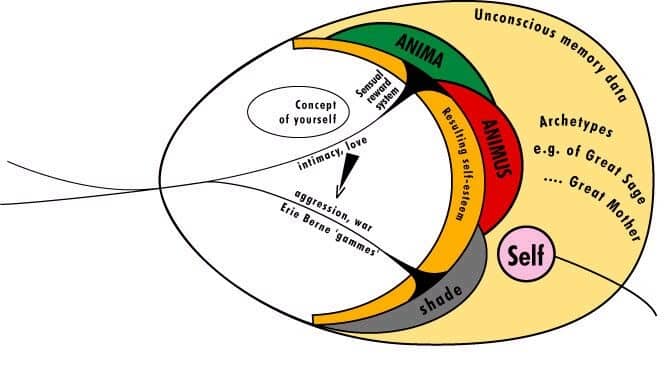

The Jungian model of the psyche. Here the shadow self is referred to as the “shade.” Click image for more info. (Source)

If You Want to Save the World, Tend to Your Shadow Self

“If you imagine someone who is brave enough to withdraw all his projections, then you get an individual who is conscious of a pretty thick shadow. Such a man has saddled himself with new problems and conflicts. He has become a serious problem to himself, as he is now unable to say that they do this or that, they are wrong, and they must be fought against… Such a man knows that whatever is wrong in the world is in himself, and if he only learns to deal with his own shadow he has done something real for the world. He has succeeded in shouldering at least an infinitesimal part of the gigantic, unsolved social problems of our day.”

— Carl Jung, Psychology and Religion (1938)

While shadow work is a rewarding way to cultivate a deep and intimate understanding of ourselves, and thus evolve as individuals, the truth is that the world needs us to embark on this journey sooner rather than later. The collective shadow houses society’s basest impulses: those of greed, hatred, and violence. If one person acting on these impulses can do a lot of harm to others, what happens when we act on them as a collective?

We can see the answer manifest in our world today. Unfettered greed leads to a stop-at-nothing drive to boost profits, which takes its toll on the Earth as we alter ecosystems and climate patterns to exhaust natural resources. Regional violence escalates in the areas affected by famine, drought, and climate disasters that irresponsible consumer practices, overpopulation, and industrialization create. The poor become poorer as corporate interests sway public opinion to form policies that benefit the rich at the expense of everyone else—especially those who are most disadvantaged.

We hate and fear what we don’t understand, prompting us to pursue violence against people rather than seek diplomatic solutions with one another. We project our own worst qualities onto our enemies to justify the violence against them. We hoard resources, ignore the suffering of others, and continue the patterns of behavior that pollute the world we all call home.

These behaviors are not exclusive to the Western world, or to the Middle East, or South America, Africa, or any one region or people. We all do it, either by participating in the entities directly involved in the conflicts, or by allowing them to continue through our own inaction.

While these large-scale problems may seem impossible for any one person to influence, we each have more power in this game than we may think. For all our discussion of the abstract power of societies, they are still made up of individual people. When two people connect, they form a relationship. A group of relationships forms a community, and the place where communities intersect is what we come to know as society.

Each of us is responsible for forming the social codes of our communities. Racism, for example, is a huge issue in the United States in the present moment and Americans are struggling to find a way to correct this prejudice and the inequality it creates. Whereas previously racism was a way to structure American society, modern Americans have decided this racial hierarchy is no longer appropriate. So, now, when people call out and denounce racism in their communities, they establish that racism is not an acceptable part of the social code. On the other hand, people who practice racism establish that it is appropriate, and people who ignore racism enable it.

Every day, you are building the culture of your community. When you smile at strangers, you promote a culture of kindness and connection. If you avoid making eye contact or speak to others coldly, you build a community based on distrust and animosity.

Our actions extend far beyond ourselves—they have a ripple effect on society as a whole. Consider cities like New York that have a reputation for being “rude.” Can a city really be rude? No, of course not—but all the individual people living there can.

Unfriendly communities are not hostile because of just one or two people, but because the majority of people act that way. When you have a large group of people living in close proximity all projecting and acting out their unconscious impulses on one another, the result is a toxic culture. People who hurt each other stop trusting one another, and without trust, communities fall apart and individuals become isolated.

However, this wave can be countered with a conscious effort to breed trust, connection, and kindness.

These connections rebuild fragmented communities, helping us to overcome our isolation and tap into a collective or community mentality. When this happens we stop thinking selfishly and start thinking empathetically and cooperatively. As loving, healthy communities connect with one another, they work together to create public policies that benefit more people, extend help to those who need it, and work to preserve the natural world they inhabit.

And this all begins with you.

When you work to heal and integrate your shadow, you find that you stop living so reactively and unconsciously, thereby hurting others less. You build trust in your relationships, and the people whose lives you touch open themselves to others, building even more healthy relationships. Even random acts of kindness to strangers will increase the likelihood that they will be kind to strangers in turn, which will lighten the mood of a community overall.

You hold within you the power to catalyze a ripple that will vibrate through the lives of the people around you. The world desperately needs more kindness, more trust, and more cooperation to heal divisions, address pressing global issues, and avoid catastrophes that could lead to the extinction of humanity and many other species. Doing deep inner work may seem like a self-absorbed process, but you’ll come to find that, at its core, it truly becomes about so much more than just you.

Save your shadow self, save the world.

Read Part Two of this series by Jack E. Othon.