If you feel like you have martyr syndrome, the good news is there are things you can do to overcome it and start living a happier, more positive life. By learning to express your feelings more, challenge negative beliefs and expectations, and set some healthy boundaries, you’ll quickly start to notice a big difference in how you feel about yourself, your circumstances, and other people. If you’re not quite sure where to start, don’t worry—this article will help guide you through the process of addressing your martyr syndrome and overcoming it.

Expressing Your Needs  Download Article

Download Article

-

1Stop expecting others to read your mind. If other people were going to understand your needs without you telling them, they would have understood by now. Good communication skills involve both speaking and listening. A simple conversation can clear up a big misunderstanding. If you’re trying to express yourself via pouting, sulking, or otherwise acting out, you cannot expect to be understood. Recognize that the only way another person will understand you is if you reach out to that person.[1]

1Stop expecting others to read your mind. If other people were going to understand your needs without you telling them, they would have understood by now. Good communication skills involve both speaking and listening. A simple conversation can clear up a big misunderstanding. If you’re trying to express yourself via pouting, sulking, or otherwise acting out, you cannot expect to be understood. Recognize that the only way another person will understand you is if you reach out to that person.[1]- For example, you feel you’re being asked to do too much at work. Have you told people in your office you need help or have you simply acted cold towards others?

- If you have not told anyone you need help on a project, chances are they don’t know. Being cold towards your co-workers is not really communication and, chances are, no one knows what the problem is on your end.

-

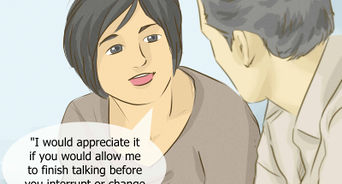

2State your feelings directly. The first step to direct communication is stating your feelings. When expressing yourself, focus on what you’re feeling. Try to abandon any mentalities you have convincing yourself you’re inherently the victim or things are inherently stacked against. All you can know for sure are your own feelings, so focus on expressing these.[2]

2State your feelings directly. The first step to direct communication is stating your feelings. When expressing yourself, focus on what you’re feeling. Try to abandon any mentalities you have convincing yourself you’re inherently the victim or things are inherently stacked against. All you can know for sure are your own feelings, so focus on expressing these.[2]- Start with the words, “I feel…” when expressing yourself and then briefly state your feelings and the behaviors causing them. This reduces blame as you’re focusing on your personal reactions over objective facts.

- For example, do not say, “You guys gave me too short notice for this project and now I have to work harder than everyone else in the office.” Instead, say something like, “I feel overwhelmed because I didn’t get enough notice about the project.”[3]

- Focus on the present moment. Express how you feel now. Do not let past emotions or problems control how you act now.

-

3Express your needs. People with martyr syndrome may hesitate to express their needs or ask for help.[4] Rather than reaching out and explaining what people can do to help, you may prefer to view your situation as hopeless and harbor resentments. However, this is unhealthy long term and can lead to strained personal and professional relationships. If you need something, say so.[5]

3Express your needs. People with martyr syndrome may hesitate to express their needs or ask for help.[4] Rather than reaching out and explaining what people can do to help, you may prefer to view your situation as hopeless and harbor resentments. However, this is unhealthy long term and can lead to strained personal and professional relationships. If you need something, say so.[5]- For example, if you need help, just ask. Say something like, “I could really use some extra help on this project if any of you have any downtime.”

-

4Avoid escape mechanisms. People with martyr syndrome may have built in escape mechanisms to help them avoid communication. If you are frustrated or upset by a situation, think about the ways you handle that other than communicating directly. Learn to recognize and avoid these mechanisms to begin with.[6]

4Avoid escape mechanisms. People with martyr syndrome may have built in escape mechanisms to help them avoid communication. If you are frustrated or upset by a situation, think about the ways you handle that other than communicating directly. Learn to recognize and avoid these mechanisms to begin with.[6]- Some people may behave in a negative fashion in order to entice others to guess what’s wrong. Instead of expressing yourself directly, for example, you may sulk or act cold towards someone who’s upset you.

- You also may complain about the issue in ineffective ways. For example, you may whine or complain continually, refusing to listen to advice or suggestions. You may also complain to other people around the person who’s frustrating or upsetting you while withholding information from them.

- You may also find excuses for not communicating. For example, you will convince yourself you’re too tired or too busy to talk things out directly.

- Writing in a journal is a great way to confront your daily life and to process your emotions in a healthy way.

Changing Your Thought Patterns  Download Article

Download Article

-

1Examine your own feelings. Understanding the causes and issues behind your martyrdom can help you make positive changes in your life. Try to get into touch with your own emotional state. Question why you might act like a martyr. If you can identify the cause, you can identify the solution.

1Examine your own feelings. Understanding the causes and issues behind your martyrdom can help you make positive changes in your life. Try to get into touch with your own emotional state. Question why you might act like a martyr. If you can identify the cause, you can identify the solution.- Do you have low self-esteem? Do you ever find yourself thinking that you are worthless or unable to control your own life?

- When you feel upset, can you identify what is causing it? Or are you unsure?

- Do you often hold grudges? Is there something from the past that you can’t let go of?

- Do you often see situations as hopeless? Why is this? Does it help you avoid uncomfortable situations? Does it help you justify your current state of life?

-

2Recognize you have choices. Martyr syndrome is often marked by a feeling of helplessness. You may feel you are inherently the victim in life and that will not change. While there is a lot one cannot change about any given situation, learn to recognize where you can make choices. This will help you feel more in control of your life.[7]

2Recognize you have choices. Martyr syndrome is often marked by a feeling of helplessness. You may feel you are inherently the victim in life and that will not change. While there is a lot one cannot change about any given situation, learn to recognize where you can make choices. This will help you feel more in control of your life.[7]- For example, everyone finds their job stressful at times. Having to do things you dislike at work is part of life, and you cannot fully control stressful situations from occurring. However, you can control your reactions and coping mechanisms.

- The next time you encounter stress at work, pause and remember you have choices. Think to yourself, “I can’t completely get rid of these stressors, but I can control how I react. I can make a choice to stay calm and deal with this effectively.”

- When faced with a difficult situation, sit down, and make a list of everything that you can do to make a difference. This will help you feel as though you have more control in your life.

-

3Stop expecting to be rewarded for your suffering. Some people volunteer to endure pain and neglect with the hope of being rewarded somehow. People feel that being a martyr will lead to things like recognition, love, or other rewards. Think about how you expect to be rewarded for your martyrdom.[8]

3Stop expecting to be rewarded for your suffering. Some people volunteer to endure pain and neglect with the hope of being rewarded somehow. People feel that being a martyr will lead to things like recognition, love, or other rewards. Think about how you expect to be rewarded for your martyrdom.[8]- Think about how often you talk to other people about your martyrdom. Do you think that you use this behavior to get attention from others?

- Many people are relationship martyrs. You may find yourself putting a lot more into a relationship than you’re receiving. Oftentimes, people feel giving and giving to difficult people will eventually result in those people changing and becoming more loving and caring.

- Ask yourself whether this has ever really happened. In most cases, giving more than you receive in a relationship does not result in the other person changing. It only builds resentments and frustrations on your end.

-

4Identify your unspoken expectations. People with martyr syndrome often expect a lot from others. You have ideas of how people should behave that are not always reasonable or realistic. If you find yourself frequently feeling victimized by others, pause and check your own expectations.[9]

4Identify your unspoken expectations. People with martyr syndrome often expect a lot from others. You have ideas of how people should behave that are not always reasonable or realistic. If you find yourself frequently feeling victimized by others, pause and check your own expectations.[9]- Think about demands you place on others. Ask yourself what you expect from people around you and whether these demands are reasonable.

- For example, in a romantic relationship, you may expect your partner to match you in certain ways. Say you prefer working out with your partner, but your partner prefers to work out alone. You may find yourself assuming you’re the victim. You may feel your partner should want to spend time with you so they’re automatically in the wrong.

- Ask yourself whether this is really reasonable. If you’re unsure, you can ask a trusted family member or friend for their perspective.

-

5Examine your beliefs. Martyrdom is closely associated with certain religious and philosophical beliefs. If you have martyr syndrome, it may be related to your underlying worldview. Think about whether you choose to suffer for your beliefs. Consider whether you’re trying to live up to an impossible standard or demanding perfection from yourself.

5Examine your beliefs. Martyrdom is closely associated with certain religious and philosophical beliefs. If you have martyr syndrome, it may be related to your underlying worldview. Think about whether you choose to suffer for your beliefs. Consider whether you’re trying to live up to an impossible standard or demanding perfection from yourself.- If you feel guilt, spend some time examining how you view the world. Your worldview could contribute to your martyr syndrome.[10]

Cutting Back on Your Work Load  Download Article

Download Article

-

1Lower your standards. Many people with martyr syndrome feel overwhelmed or victimized because they both take on too much and expect a lot from those around them. Ask yourself what you expect from yourself and examine whether this is realistic.

1Lower your standards. Many people with martyr syndrome feel overwhelmed or victimized because they both take on too much and expect a lot from those around them. Ask yourself what you expect from yourself and examine whether this is realistic.- What you expect of yourself is often the same as what you expect from others. Adjust your expectations to a more reasonable level. This will improve both your relationship with yourself and others.

- Accept not everything will turn out the way you wanted. If you expected yourself to complete a certain amount of work within the day, do not beat yourself up if you miss the mark. Instead, appreciate what you did get done.

- Appreciate others for what they do, even if they don’t meet your exact expectations. For example, say your spouse brings home the wrong brand of toothpaste from the store. Instead of getting angry, be appreciative that you have toothpaste at all and this is one less thing for you to do.

-

2Focus on spending quality time with others. Rather than running yourself ragged all the time, spend time with others. This will help you learn to appreciate people in and of themselves, regardless of whether they meet your expectations. Strive for small relaxing interactions, such as chatting over lunch, as well as taking a day off to unwind with friends and family members.[11]

2Focus on spending quality time with others. Rather than running yourself ragged all the time, spend time with others. This will help you learn to appreciate people in and of themselves, regardless of whether they meet your expectations. Strive for small relaxing interactions, such as chatting over lunch, as well as taking a day off to unwind with friends and family members.[11]- Keep in mind that not everyone is good company. If certain family members or classmates make you feel bad about yourself, don’t spend time with them.

- Focus on spending time with people who make you feel happy and relaxed. Avoid people who drain too much of your energy, as interactions with them may leave you tired.

-

3Seek help from others. People with martyr complex may convince themselves they cannot ask for help. If you feel the inclination to ask someone for help, you may find yourself making excuses as to stop yourself from reaching out. For example, you may convince yourself that person is too busy or that you don’t want to burden them. Remember everyone needs help sometimes and there’s no shame in reaching out.

3Seek help from others. People with martyr complex may convince themselves they cannot ask for help. If you feel the inclination to ask someone for help, you may find yourself making excuses as to stop yourself from reaching out. For example, you may convince yourself that person is too busy or that you don’t want to burden them. Remember everyone needs help sometimes and there’s no shame in reaching out.- The worst that can happen is that someone will say “No.” Even if someone is unable to help, they probably will not think less of you for having to ask for help. Almost everyone has needed to reach out to others for help at some point.

-

4Learn to set effective boundaries. Every time you say yes when you mean no, you’re sabotaging yourself. You can learn to politely and respectfully decline to do what people ask you do. Before you agree to someone’s request, ask yourself some questions. Ask yourself if you truly have time. Commitment should make you feel good about yourself and not bitter and overwhelmed.[12]

4Learn to set effective boundaries. Every time you say yes when you mean no, you’re sabotaging yourself. You can learn to politely and respectfully decline to do what people ask you do. Before you agree to someone’s request, ask yourself some questions. Ask yourself if you truly have time. Commitment should make you feel good about yourself and not bitter and overwhelmed.[12]- You can say “no” without ever actually saying “no.” For example, you can say, “Sorry, I can’t commit to that right now” or “I already have plans.”

- Think about the commitments that really make you happy and prioritize them over things that drain you. Say “Yes” that things that will make you feel personally fulfilled and pass on other commitments.

-

5Do something for yourself every day. Even if it’s something small, doing something for yourself every day can help you feel like less of martyr. Find ways to give yourself a small treat. For example, take half an hour before bed every night to unwind with a book.[13]

5Do something for yourself every day. Even if it’s something small, doing something for yourself every day can help you feel like less of martyr. Find ways to give yourself a small treat. For example, take half an hour before bed every night to unwind with a book.[13]- Make it a ritual or a habit, such as spending an extra 5 minutes in the shower, relaxing, or meditating in the morning.

- Consider treating yourself to something bigger once every week or so, such as a manicure or bubble bath.

References

- ↑ https://psychology-spot.com/martyr-complex/

- ↑ https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/fearless-you/201307/are-you-relationship-martyr

- ↑ https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/articles/200603/tame-your-passive-aggression

- ↑ Elizabeth Weiss, PsyD. Clinical Psychologist. Expert Interview. 26 July 2019.

- ↑ https://psychology-spot.com/martyr-complex/

- ↑ https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/fearless-you/201307/are-you-relationship-martyr

- ↑ https://blogs.psychcentral.com/imperfect/2016/10/martyr-complex-how-to-stop-feeling-like-a-victim-create-healthy-relationships/

- ↑ https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/fearless-you/201307/are-you-relationship-martyr

- ↑ https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/fearless-you/201307/are-you-relationship-martyr

About This Article

Did this article help you?

-max_bytes(150000)-strip_icc()-format(webp)/gettyimages-1126484970-ee992b9c471340afb7f0634bd03fada9-resize-299-224-ssl-1.jpg?ssl=1)

-max_bytes(150000)-strip_icc()/elizabeth-mcgrory-1000-0dcae19a0c394bc18ebb137312c17247-resize-357-357-ssl-1.jpg?ssl=1)

-max_bytes(150000)-strip_icc()-format(webp)/questions-590b68a03df78c9283acf4bc-w-840-ssl-1.jpg?ssl=1)

-max_bytes(150000)-strip_icc()-format(webp)/holdinghands-590b6bd83df78c9283ad0648-w-840-ssl-1.jpg?ssl=1)

-max_bytes(150000)-strip_icc()-format(webp)/memory-590b6d225f9b586470a9b886-w-840-ssl-1.jpg?ssl=1)

-max_bytes(150000)-strip_icc()-format(webp)/teeth-590b6e1f5f9b586470a9c277-w-840-ssl-1.jpg?ssl=1)

-max_bytes(150000)-strip_icc()-format(webp)/smile-590b6f8e3df78c9283ad2f76-w-840-ssl-1.jpg?ssl=1)

-max_bytes(150000)-strip_icc()-format(webp)/bucket-590b70f15f9b586470a9d3d8-w-840-ssl-1.jpg?ssl=1)