Category: EMDR / TRAUMA

Emotional Flashbacks: What They Feel Like, And How To Cope With Them

Privacy Overview

EMDR in a Nutshell: Healing from Trauma

What Is EMDR?

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is a guided process that supports trauma work by using “bilateral stimulation” (BLS), or stimulating each hemisphere of the brain alternately via the senses. EMDR also involves talking, deep breathing, and other ways of grounding the nervous system. (“To ground” the nervous system means to bring its level of activation back or closer to the “ground” or baseline level.)

There are many kinds of BLS that can work well, although eye movements have been shown to be the most effective. In my practice, I use a combination of eye movements (watching a light or my finger moving back and forth), as well as sounds alternating in each ear through headphones—whichever the client prefers.

When we first meet, I work together with my client to figure out what combination of sounds and colors feels best. (A person’s own report is the best indicator for what kind of stimulation works best for them.)

Rather than medicalizing distress, EMDR provides a way of healing from trauma. EMDR isn’t about trying to treat the symptoms of an illness. It’s about healing from the root cause.

What Can EMDR Treat, and What Is It Not Helpful for?

EMDR can be very useful for trauma, specific anxieties and phobias, and many forms of impact left behind by difficult experiences or relational patterns. EMDR can be effective for Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD) and developmental traumas.

Another form of EMDR called Eye Movement Desensitization (EMD) can be helpful to reduce distress due to overwhelming or complex traumas and triggers, which can be used in place of or in preparation for additional reprocessing.

EMDR can be used to prepare for specific future actions (public speaking being one common example).

It is even possible to use EMDR for memories that may be vague, pre-verbal, or otherwise not fully available to consciousness. This is accomplished by processing the physical responses and triggers we have in the present.

EMDR is less directly useful for depression, grief, the impact of neglect, and other experiences we might characterize with the word “lack.” Many or most forms of difficult human experience involve both fear and loss, and working on the somatic or body-based reactivity to trauma with EMDR can allow grief work to become tolerable. In other words, EMDR can open the way for other therapies (such as psychodynamic, existential, and other “talk” therapies) to be more effective.

What Is the Difference Between a Traumatic Memory and Other Memories?

Each memory we have is stored in a “neural tree,” which (in theory) is a structure of cells that we could pick up and look at. Our non-traumatic or ordinary memories have many “branches” into the frontal cortex of the brain, which allows us to describe the memory with language, and into the hippocampus, which allows us to put the experience into the context of time (i.e. we know it happened in the past and therefore that it is now over).

Conversely, the neural trees of traumatic memories have fewer of these branches, and they also have a greater number of “roots” that anchor them to the amygdala, which is the fight/flight/freeze center of the brain. (“Freezing”, or dissociation, can be thought of as a protective numbing response to the “fight or flight” responses of anger, anxiety and fear. “Drifty,” “numb,” and “confused” are some words clients who experience dissociation have used to describe how it feels to them.)

This makes it much easier for a traumatic memory to activate the adrenal glands, and thereby the threat response system throughout the whole body. This is what we mean when we colloquially use the word “trigger”: the body has been activated for survival in response to a present stimulus that is meaningfully reminiscent of the past.

What Is Trauma Work?

“Trauma work,” “trauma processing,” or just “processing” are all shorthand ways we refer to helping neural trees grow more branches and untwine their roots! EMDR can make this process much easier and faster, though the process itself is ancient. We say that the brain “knows” how to heal itself, much like how the skin “knows” how to heal a cut. EMDR gives the brain support—much like how antiseptics and bandages can support healing wounds of the skin.

As we said above, unprocessed traumatic memories are less connected to the frontal cortex. This means we have less ability to use language to “look at” the memory, instead of “be in it,” and it’s much harder for our systems to believe that the memory is in the past and that the threat is over—it can feel like it’s happening all over again. “Naming it to tame it,” or putting experience into words (which, in EMDR, happens between doses or “sets” of BLS), helps grow more connections to the frontal cortex.

Another reason doing trauma work is one of the greatest challenges we face is because the brain and body don’t have a system that tells us we are in “mild distress.” We can only adjust between “life and death (fight, flight or freeze)” and “calm (rest and digest).” Recalling traumatic memories, alternating with taking breaks, helps the “roots” into the amygdala unwind and the survival system to quiet.

So even contemplating trauma work can feel like life and death! It’s important to be aware that there’s a reason for this intensity, and that after successful processing, it will fade. Working on trauma is not likely to be comfortable, but if it is not tolerable for my client, we stop (using a stop signal we agree on before we begin). If that happens, we focus on support and using grounding skills until their nervous system is closer to baseline. Trauma work is not as hard as trauma!

How Does EMDR Work?

EMDR allows us to process trauma by activating traumatic memories at the same time as it gives the nervous system cues for safety. This creates an “in and out” rhythm, which helps the brain get back in sync, and supports your brain in building connections to the neurons that store these memories.

We have data that clearly show that EMDR gets good results. Science is still exploring the reasons why EMDR works, but here are some of the most popular current theories, one or all of which could be true:

- The back-and-forth visual motion communicates to the amygdala that your body is in motion, which tells the brain that it is safe, active, and not trapped.

- The ocular nerve or other sense organs are stimulated, the activity of which facilitates rewriting (basically, it gets the area “warmed up” and ready for change).

- Stimulation of the sense organs takes up some of the brain’s bandwidth and resources (such as oxygen and glucose), which means less is available to fuel panic responses.

- The eye moments mimic what happens in REM sleep, another time when the brain is processing and storing memories. (This process is not fully understood, but it’s theorized to be similar to how EMDR and BLS work.)

- Trauma disrupts the natural rhythm of brainwaves, and EMDR provides a “corrective” rhythm to resonate with the brain as it processes disruptive memories.

- Predictable structure while talking about trauma is distracting and calming.

Any form of verbalizing trauma while in the regulating presence of a trusted other will have beneficial effects, for at least two reasons. First, “If you can name it, you can tame it”: Language activates the frontal cortex, which helps to build neural bridges, as well as causing a release of endorphins and other soothing neurotransmitters.

Second, our nervous systems are built from birth to monitor the internal state of others (including breath and pulse rates), and to resonate with them—so sharing a story with someone who is calm can help us calm ourselves while we tell it.

What Happens During an EMDR Session?

EMDR has a few different phases. In the first phase, I lay the groundwork with my client, including practicing grounding skills, setting up a stop signal, getting more familiar with BLS, and making sure they have a crisis plan and other supports in place in case they need help between sessions.

Next, we work together to come up with some “headlines” of memories to target, and explore the client’s feelings and beliefs about these memories. This doesn’t mean it’s not ok if we discover more along the way, but it can help us find some good places to start. In fact, we might say that it’s more likely than not that other memories will come up. That’s neither good nor bad, it’s just the brain going through the networks of association it has.

If relevant, we may also set goals at this point for a future action the person is working towards.

Most often, BLS is not used until session two (although this does not mean that processing cannot begin in your brain before that!). At that point, I work with the person to bring up the memory we agreed to use as a starting point, paying attention to the sense information, body feelings, and emotions that go with the memory.

Then, we do about 20 to 30 seconds of BLS. During that time, I ask my clients to “just notice,” “go with,” or “follow” what they’re noticing inside themselves. At the end of every “set,” I ask them to take a deep breath, tell me a sentence or two about what they’re noticing, and then we repeat.

It’s kind of like you’re on a train ride, and I’m on the phone with you, asking you what you see out the window.

Sometimes, what a person feels and notices from set to set will change, and sometimes it won’t. It’s even perfectly normal to have periods of feeling nothing at all. This is often the brain’s way of resting, assessing safety and connection, or otherwise taking care of you, and sometimes the best thing to do is just notice that feeling for a few minutes.

Although I keep a close eye on how my client is feeling as we go, I trust their own report most of all—as a person is their own best guide to how they’re doing. Some experiences are not always visible from the outside, such as “red lining” (panic, fury, etc.) or “blue lining” (dissociating).

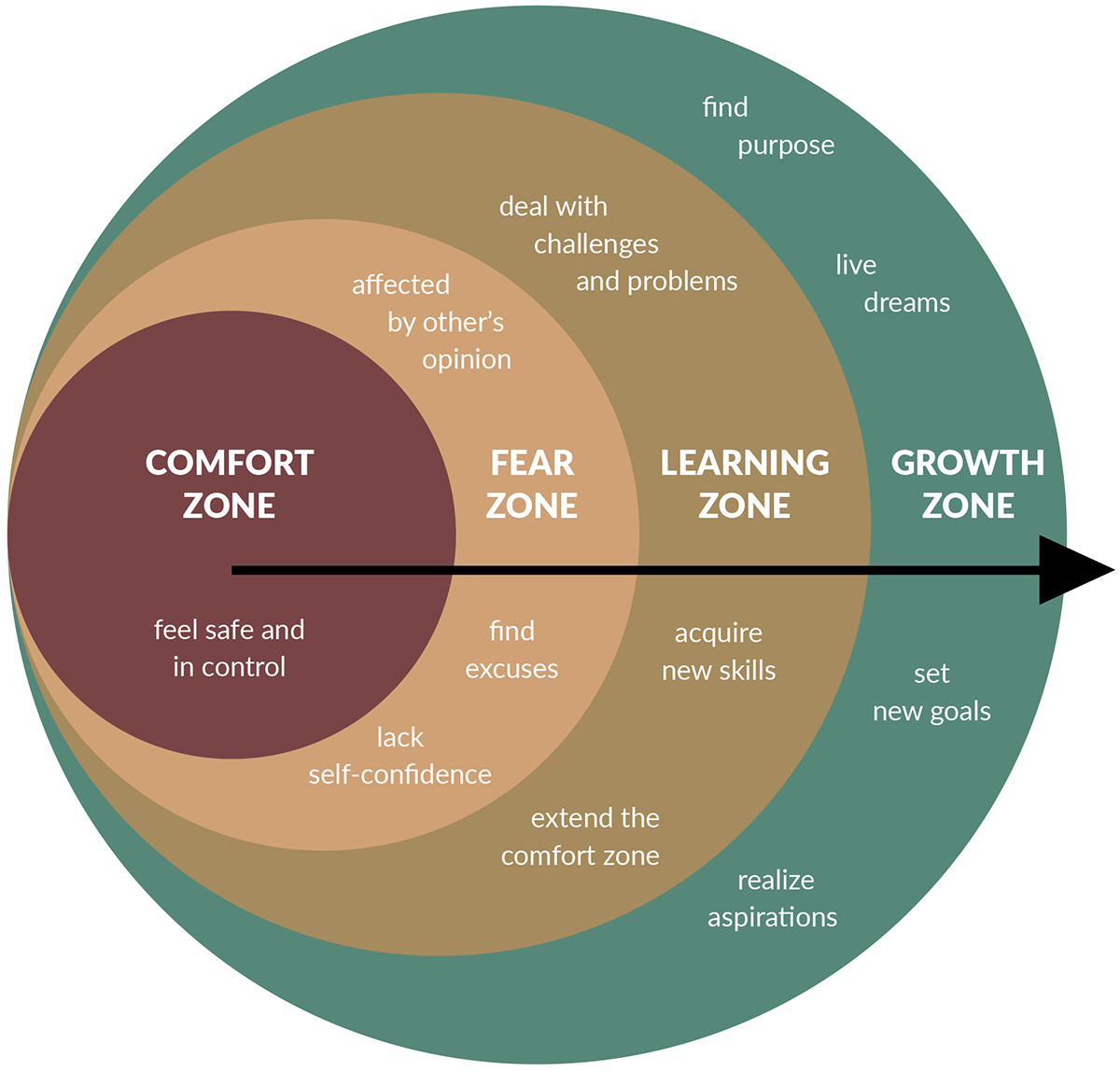

I always tell my clients that if they think they’re feeling too much or too little, or are otherwise outside of their “zone of tolerance,” it’s important for the healing of their nervous system that they let me know. That way, we can take a break and use grounding skills before we continue.

Most sessions are spent doing sets for about 20 to 40 minutes. At the end of every session, we wrap up by using grounding skills to return the person’s nervous system to a tolerable state. I also ask if there’s anything they want to “leave in the container of therapy” (which doesn’t mean it won’t come to mind between sessions, but rather that they will set the intention not to continue to focus on it). Then we check in for a minute or two so we can both share thoughts and observations about the session.

Reprocessing can take several sessions. On average, it ranges from 3 to 12 weeks, though it can be significantly shorter or longer. Sometimes a person may feel different by the end of a session, and sometimes they may not.

What Do I Do Between Sessions?

In between sessions, clients may continue to process memories, meaning they may still be remembering, feeling, or even dreaming things. If that happens, their job is to notice it as much or as little as they’d like to, and then use a grounding skill. (“They don’t work if you don’t use them!”)

The client’s most important job, and their only “homework,” is to keep their nervous system and emotions within tolerable limits as much as they can. (It’s ok if they can’t do this perfectly, but it’s important to set it as a goal to strive towards.)

There are a number of questions we check in about as we prepare to engage in EMDR:

- How will you know if you’re outside of your tolerable zone?

- What grounding skills will you use?

- What friends and family can you connect with, whether to ask for help using grounding skills, talk about what you’re feeling, or just to share space?

- If you are unable to ground yourself on your own or with the assistance of loved ones, what hotlines and/or mental health professionals will you call and how?

What Might Be Different After EMDR Is Complete?

The good and bad news is that EMDR does not make you forget what has happened. After processing, accessing memories of a traumatizing event will feel much like accessing any other memory. The most noticeable difference will likely be that the memory no longer creates an overwhelming body response.

After EMDR, it’s common for a phase of grief work to begin. This can involve feeling sadness and anger, as well as (in some cases) shifts in sense of identity or what is important to us. Sometimes we need support to explore questions like “Who am I without this fear?” or “Is it ok to get better?” Continuing in talk therapy after EMDR is over may help people continue to integrate their experiences and to heal.

To anyone contemplating EMDR, I wish you good healing, and congratulations to anyone who is willing to take the risks to talk about the hard stuff. I believe the greatest gift we can give to ourselves and to others is to make room for our feelings.

Fawn Response: A Trauma Response + The Reason for People-Pleasing Behavior | Modern Intimacy

Source: Fawn Response: A Trauma Response + The Reason for People-Pleasing Behavior | Modern Intimacy

When the going gets tough in your relationships, what is your gut reaction? Do you feel like you spend most of your time pleasing other people? Or do you have a hard time knowing how to meet your needs? Maybe you feel like you don’t see a fight response or flight response in yourself, but you notice one of the two lesser-known responses: the freeze and fawn responses.

You might be wondering, what exactly are the freeze and fawn responses? Two of the four trauma responses (fight, flight, freeze, and fawn) that can stem from childhood trauma, and they both involve symptoms of PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder). A fawn response occurs when a person’s brain acts as if they unconsciously perceive a threat, and compels survival behavior that keeps them under the radar.

What is the Freeze Response?

This response is paralyzing. You are so overwhelmed by fear that your body stops.

You stop thinking, stop moving, and, in some cases, stop breathing.

Because your body stops, it is an unconscious act of dissociation with whatever is happening around you. This response is also associated with “shell shock” or basic post-traumatic reactions. If you have the “freeze” response early in life, you may be predisposed to experience freeze symptoms later in life.

What is the Fawn Response?

Different from the fight, flight and freeze responses, the fawn response points to people-pleasing.

Though people-pleasing is not the only manifestation of fawning, it tends to be the most evident sign.

Pete Walker was a pioneer in defining “fawning.” Walker says this response is developed in childhood to avoid mistreatment from adults.

Fawn responses can be any number of things but are nervous attempts to deflect attention. This can mean flattery, admission to toxic relationships, or complete destruction of personal boundaries.

People who fawn tend to deny their preferences and boundaries to make other people happy. They unconsciously believe that the price for relational security is compliance. They think that if they make others happy, they will be in less danger.

Do I Show the Fawn Response?

Sometimes those who show the fawn response don’t even know they are fawning, and they have likely experienced positive feedback from others in return, so it may not register as a problematic behavior.

Think you may fall into this category? Think back to any time conflict has come up. You can start by asking yourself these questions to find out:

Do I put my needs aside to make others feel better?

Do I feel empty in relationships after giving too much of myself?

Do I avoid conflict at all costs?

Do I feel everyone’s emotions all at once?

Do I think I am responsible for making everyone happy?

If you answered yes to more than two of these questions, it is likely your default is the fawn response.

Why Do I Have a Fawn Response?

There is not a short answer to why someone may show the fawn response. Generally, those that fawn are extremely empathetic and would rather take the emotional blow than someone else, the price of admission in relationships, and fawn types seek safety in interpersonal dynamics.

The most popular theory on fawning comes from Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs.) These are events usually happen before the child is eighteen years old and can impair children for the rest of their lives.

Adverse Childhood Experiences can range from poverty to neglect to abuse at home. Continuances of these events can establish negative thought patterns early-on.

When our brains are still developing, we will do anything to avoid danger. The fawn response is to seek safety by merging with the perpetrator. So as children, we do what we are told, even if it isn’t what is right or good for us.

This response invokes strategies from “flight,” “flight,” and the “freeze” responses, so it is seen as the most adaptive reaction. Fawning requires knowledge of whomever is hurting you and skill to know how to appease them. It is often seen in people who endure narcissistic abuse.

Fawning is also sometimes associated with codependency. Both are emotional responses that are triggered by complex PTSD.

In both fawning and codependency, your brain thinks you will be left alone and helpless. The brain’s response is to then attach yourself to a person so they think they need you. This can lead to do things to make them happy to cause less of a threat to yourself.

Though, the threat is the variable in each scenario. In fawning, the threat could be social isolation, conflict with a loved one, or unhappiness. Codependency is generally paired with loneliness.

How Can I Help My Fawn Response?

Trauma affects everyone, not just the one experiencing the trauma.

It affects the one inflicting the trauma, the one affected by the event, and anyone who interacts with those people.

The fawn response is a great example of this since it involves submitting to what others want.

So, how can you begin healing from trauma?

Observe Yourself

One of the first things to do to stop fawning behaviors is to observe them.

Whenever you are triggered, think about these things:

Why am I fawning right now?

How am I experiencing fawning behaviors?

How do I feel right now?

What do I want to do right now, not how do I think I need to react?

Asking yourself these questions will begin to unlock the trauma-affected regions of your brain.

Therapy

A next possible step is to enroll in therapy appointments. Being able to share your trauma with a professional can help you process. Not only will you have a listener, but someone who can offer science-backed suggestions!

There are several different methods for healing trauma, including the Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) process. This system helps re-wire your brain, creating new neurological pathways that help you react to trauma when it comes up.

Taking stock of your fawning behaviors before going to therapy is good. You can fill your therapist in on the issues since they likely will not see your trauma responses themselves.

Many times, you learn about traumas you weren’t didn’t even know were affecting you.

Find a Safe Person

Aside from a therapist, find a person you can talk with about your recovery. This can be a friend or family member that can hold you accountable.

As you’re healing, they will ensure you continue taking steps to stop fawning behaviors. But, they will also be the first ones you call when you’re struggling!

Next Steps

If you are ready to face your fawn response, to improve your mental health, there are many steps you can take. Begin thinking on ways to stop your fawning behaviors and how to ask for help from trusted people. There is no need to be obsessive compulsive about it, though. The main thing to remember is that other people have benefited from your fawn response, so they may have reactions to your changes.

Don’t worry, you can open up little by little and practicing the art of saying no more readily. Grab a cute mug that promotes positivity and healing. Write something that describes how you’ve been feeling. Or, try a yoga class to deepen your mind-body connection.

Author Bio

FREE 30 MIN INITIAL CONSULTATION WITH

MODERN INTIMACY …

You May Also Like…

The Reality of Military Sexual Trauma & What To Do

Members of the armed forces experience stress that ordinary civilians do not. Imagine being a part…

The Orgasm Gap: Solutions for Boosting Sexual Pleasure

Everyone deserves an exhilarating sex life. While orgasms aren’t the only source of pleasure…

10 Internalized Misogyny Books That Can Set You Free From the Patriarchy

Did you know that feminism is the belief that both sexes should have equal opportunity in all…

0 Comments

Submit a Comment

LET’S WORK TOGETHER

WANT TO WRITE FOR MODERN INTIMACY?

What are the signs and symptoms of dissociation and dissociative disorder?

Source: What are the signs and symptoms of dissociation and dissociative disorder?

Dissociation and dissociative identity disorder (DID)

This section gives information about dissociation and dissociative disorders. It explains the different dissociative disorders, their symptoms and treatments. This section is for anyone with dissociation and dissociative disorder and their carers, friends or relatives.

Overview

- If you dissociate you might have symptoms such as not feeling connected to your own body or developing different identities.

- Dissociative disorder is a mental illness that affects the way you think. You may have the symptoms of dissociation, without having a dissociative disorder. You may have the symptoms of dissociation as part of another mental illness.

- There are lots of different causes of dissociative disorders.

- You may get talking therapies for dissociative disorders.

- You may be given medication that may help with symptoms of dissociation and dissociative disorder.

About

What is dissociation?

Many people will experience dissociation at some point in their lives. Lots of different things can cause you to dissociate. For example, you might dissociate when you are very stressed, or after something traumatic has happened to you. You might also have symptoms of dissociation as part of another mental illness like anxiety.

Some of the symptoms of dissociation include the following.

- You may forget about certain time periods, events and personal information.

- Feeling disconnected from your own body.

- Feeling disconnected from the world around you.

- You might not have a sense of who you are.

- You may have clear multiple identities.

- You may feel little or no physical pain.

You might have these symptoms for as long as the event that triggered them, or for a short time afterwards. This is called an episode.

For some people these symptoms can last for much longer. If you have a dissociative disorder you might experience these symptoms for long episodes or even constantly.

Types

What are the different types of dissociative disorder?

There are different types of dissociative disorder. There is more information on each of these below.

It‘s important to remember that you could have the symptoms of dissociation without a dissociative disorder. There is also a lot of disagreement among professionals over dissociative disorders.

What is dissociative amnesia?

If you have dissociative amnesia you might not remember things that have happened to you. This may relate to a stressful or traumatic event, but doesn’t have to.

In severe cases you might struggle to remember:

- who you are,

- what happened to you, or

- how you felt at the time of the trauma.

This isn’t the same as simply forgetting something. It is a memory ‘lapse’. This means you can’t access the memory at that time, but they are also not permanently lost.

With dissociative amnesia you might still engage with other people, such as holding conversations. You might also still remember other things and live a normal life. But you might also have flashbacks, unpleasant thoughts or nightmares about the things you struggle to remember.

You may have dissociative amnesia with dissociative fugue. This is where someone with dissociative amnesia travels or wanders somewhere else, related to the things they can’t remember. You may or may not have travelled on purpose.

What is dissociative identity disorder (DID)?

Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is sometimes called ‘Multiple Personality Disorder. But we have called it DID on this page.

If you have DID you might seem to have 2 or more different identities, called ‘alternate identities. These identities might take control at different times.

You might find that your behaviour changes depending on which identity has control. You might also have some difficulty remembering things that have happened as you switch between identities. Some people with DID are aware of their different identities, while others are not.

There is a lot of disagreement between researchers over the notion of DID.

We think of someone with DID as having different identities. But some researchers think that that these are actually different parts of one identity which aren’t working together properly.

They suggest that DID is caused by experiencing severe trauma over a long time in childhood. By experiencing trauma in childhood, you take on different identities and behaviours to protect yourself. As you grow up these behaviours become more fully formed until it looks like you have different identities. When in fact the different parts of your identity don’t work together properly.

What is other specified dissociative disorder?

With this diagnosis you might regularly have the symptoms of dissociation but not fit into any of the types.

A psychiatrist uses this diagnosis when they think the reason you dissociate is important.

The reasons they give include the following.

- You dissociate regularly and have done for a long time. You might dissociate in separate, regular episodes. Between these episodes you might not notice any changes.

- You have dissociation from coercion. This means someone else forced or persuaded you. For example, if you were brainwashed, or imprisoned for a long time.

- Your dissociation is acute. This means that your episode is short but severe. It might be because of one or more stressful events.

- You are in a dissociative trance. This means you have very little awareness of things happening around you. Or you might not respond to things and people around you because of trauma.

What is unspecified dissociative disorder?

This diagnosis is used where you dissociate but do not fit into a specific dissociative disorder.

Psychiatrists also use this diagnosis when they choose not to specify the reasons why you do not fit into a specific disorder.

Or if they don’t have enough information for a specific diagnosis. For example, after a first assessment in accident and emergency.

What are dissociative seizures?

Dissociative seizures are hard to get diagnosed. They are regularly wrongly diagnosed as epilepsy.

Dissociative disorders can also be known as non-epileptic attack disorder (NEAD).

It can be hard to tell the difference between a dissociative and epileptic seizure. An EEG can read epileptic seizures but can’t read dissociative seizures. An EEG is a test that detects electrical activity in your brain using small, metal discs attached to your scalp.

Dissociative seizures happen for psychological reasons not physical reasons.

What is depersonalisation/ derealisation disorder (DPDR)?

The feelings of depersonalisation and derealisation can be a symptom of other conditions. It has also been found among people with frontal lobe epilepsy and migraines.

But it can also be a disorder by itself. This means it is a ‘primary disorder’. There is some disagreement among professionals whether DPDR should be listed with the other dissociative disorders at all.

DPDR has some differences to other dissociative disorders. In DPDR you might not question your identity or have different identities at all. You may still be able to tell the difference between things around you. And there may be no symptoms of amnesia. Instead, with DPDR you might feel emotionally numb and questions what it feels like to live. We have explained this in more detail below.

You might have these feelings constantly rather than in episodes. It doesn’t have to have been caused by a traumatic or stressful event.

Many people think that this disorder might be more common than previously thought. This might be because of:

- a lack of information about it,

- patients who didn’t report their symptoms, and

- doctors who don’t know enough about it, meaning they underreport the condition.

With DPDR you might have symptoms of depersonalisation or derealisation or both.

Depersonalisation

With depersonalisation you might feel ‘cut off’ from yourself and your body, or like you are living in a dream. You may feel emotionally numb to memories and the things happening around you. It may feel like you are watching yourself live.

The experience of depersonalisation can be very difficult to put into words. You might say things like ‘I feel like I don’t exist anymore’ or ‘It’s as if I’m watching my life from behind glass’.

Derealisation

If you have derealisation you might feel cut off from the world around you. You might feel that things around you don’t feel real. Or they might seem foggy or lifeless.

Jane’s story

Causes

What causes dissociation?

There are different things that can cause you to dissociate. For example:

- traumatic events,

- difficult problems that cause stress, and

- difficult relationships.

Other researchers have suggested that the use of cannabis may sometimes be a cause of depersonalisation/ derealisation disorder (DPDR).

Treatment

How are dissociation and dissociative disorders treated?

Dissociation can be treated in lots of different ways. The type of treatment you get might depend on which type of disorder you have.

Can medications help?

At the moment, there are no medications for dissociative disorders themselves, although you may take medication for some symptoms.

If you have episodes of dissociation you might also have a condition such as depression or anxiety. Some medications could help with this. For example, antidepressants could be used for depressive symptoms and benzodiazepines for anxiety.

Benzodiazepines can be addictive and should be prescribed for a short period only. Benzodiazepines can make Dissociation worse.

You can find more information on:

What psychosocial treatments can help?

Talking therapies are usually recommended for dissociation. There are lots of different types of talking therapy. Different ones might be used for different dissociative disorders.

What is psychodynamic psychotherapy?

If you have DID, then your doctors may think about long-term relationally psychotherapy. This is a type of therapy where you talk about your relationships and thoughts. You might talk about your past. Your therapist can link the ways you think and act with things that have happened to you.

For DID, psychotherapy might be needed for a long time, with at least 1 session every week. This will depend on individual’s situations and on their ability and level to function, resources, support and motivation.

What is eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR)?

DID may also be helped by eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR). In EMDR you make side-to-side eye movements while talking about the trauma that happened.

Doctors must be careful when using EMDR because it could make your DID worse if not done properly. But EMDR can have benefits when it is used along with other treatment. The type of EMDR used for DID is slightly different to other conditions. So, it is important that your doctor knows about your DID before you start EMDR.

What is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)?

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is another type of talking therapy. You will talk about the way your thoughts and feelings affect you. And how your behaviours may make this worse. You focus less on the past and try to change the way you think and behave.

Parts of CBT are recommended to treat DID, by helping you to change your thoughts and behaviours that come from the trauma.

A CBT approach has also been suggested for long-lasting DPDR. If you have DPDR you might often worry about your symptoms and think you have a serious mental illness or that something is wrong with your brain. CBT may help to change this way of thinking. By reducing your anxiety and depression that comes with this worrying, it may also reduce your symptoms of DPDR.

You can find more information about ‘Talking therapies’ by clicking here.

What treatment should I be offered?

In the UK, the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) publish guidelines on physical and mental health conditions. These guidelines are a standard for NHS treatment. At the time of writing, there are no NICE guidelines on dissociation or dissociative disorders.

But this doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be offered treatment. If you think you are having any of these symptoms, then explain this to your GP. They may refer you to a psychiatrist.

You can find more about ‘GPs – What to expect from your doctor’ by clicking here.

What if I am not happy with my treatment?

If you aren’t happy with your treatment you can:

- ask for a second opinion,

- ask an advocate to help you speak to your doctor,

- contact the Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS), or

- make a complaint.

There is more information about these options below:

How do I ask for a second opinion?

If you aren’t happy with your diagnosis or treatment, speak to your doctor. If they don’t offer you any other treatment options, you can ask for a second opinion. This is where another doctor will assess you and suggest diagnoses or treatment. You don’t have a legal right to a second opinion, but your doctor might agree to one.

What is advocacy?

An advocate can help you understand your rights to treatment from the NHS. They can also help you be fully involved in decisions about your care. An advocate is separate from the NHS.

You can search online to see if there are any local advocacy services in your area. Or the Rethink Mental Illness Advice Service could search for you. You can find their details at the bottom of this page.

What is the Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS)?

The Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS) at your NHS trust can try and help you with any problems or issues you have. You can find your local PALS’ details at: www.nhs.uk/Service-Search/Patient-advice-and-liaison-services-(PALS)/LocationSearch/363.

How can I make a complaint?

If you aren’t happy with the way you have been treated, you can make a complaint. You have to make a complaint about the NHS within 12 months of what you want to complain about.

You can find more information about:

Self care & risks

What are self-care and management skills?

You can learn to manage your symptoms by looking after yourself at home. You will learn how to notice when you are becoming unwell and know what your triggers are.

Not all of the techniques here will work for everyone. It is important to try something that you enjoy and that you can commit to and that works for you.

Keeping a diary

You might find it helpful to keep a diary. You could write about how you felt over the day. Or you could write down goals that you want to achieve. You could use it as part of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

Keeping a diary isn’t for everyone. If you have depersonalisation/derealisation disorder (DPDR) you might already spend a lot of time thinking about how other people see you. A diary may make you feel worse if it forces you to think about yourself. A diary can still help but talk to your GP or a counsellor first.

Grounding techniques

These techniques can be helpful for people who have been through trauma or who regularly dissociate. They can help to ‘ground’ you in the here and now. This may help when experiencing flashbacks.

Grounding works best when it is practiced regularly. Try practicing these things every day. There are different types of grounding techniques.

Using your surroundings

To use your surroundings, look around yourself. Focus on all the details of everything that is around you. Try describing this to yourself either out loud or silently in your head. Use all of your senses.

Using words

You could try positive words or phrases about yourself. For example, ‘I am strong’ or ‘I will succeed’. Write down a few things that are meaningful and positive for you. You could carry these around with you. Try reading them to yourself or aloud if your symptoms are bad.

Using images

This is similar to using your surroundings. Try thinking of a place that you feel peaceful and safe. This can be a real or imaginary place. If it is a real place, choose somewhere that is positive with no traumatic memories. Shut your eyes and imagine that place. Focus on all of the details and all of your senses.

Using posture

Try moving into a posture that makes you feel strong. This could be standing up with your shoulders back or relaxing your shoulders. Try different postures until you find one that works for you.

Using objects

Try choosing an object that is personal to you. You should try and pick something that only has positive memories attached to it. Carry it around with you and use it to remind yourself of who you are and where you are.

Relaxation

There are lots of different ways to relax. The important thing is to find something you enjoy doing. For example, cooking, reading or gardening. You might find that meditation or mindfulness helps.

Some relaxation techniques such as meditation and mindfulness may make some people feel worse. For example, if you have DPDR you might struggle with meditation. If this is the case, try and find something else that works for you. If you have CBT, you could tell the therapist. They could help you find something that works.

Exercise and diet

There are no specific exercises that can definitely help. But you could try jogging, swimming or just trying to walk more and something that suits your ability. Trying to eat more fresh fruits and vegetables can help. You could also try to reduce the amount of fat, salt and sugar you eat. Reducing the amount of caffeine, you drink can be helpful.

Sleep

If you don’t sleep enough your symptoms might feel worse. It can take a few weeks for you to get into better sleep habits. Here are some tips for helping you sleep.

- Sleep when you feel sleepy.

- Keep your bedroom as a place for only sleeping.

- If you are lying awake in bed for a long period, get up and move around for a while.

- Avoid taking naps during the day.

- Try not to have caffeine for a few hours before you go to bed.

- Make sure you get up at the same time every day. This can help you get into a regular routine.

You can find more information about ‘Complementary and alternative treatments’ by clicking here.

What risks and complications can dissociation cause?

Some people with a dissociative disorder may also have another mental health condition, such as anxiety or depression. This is called a ‘comorbid’ condition. In some cases, this can make your dissociative disorder harder in day to day life. However, all these conditions are manageable and treatable.

You can find more information on:

Carers, friends & family

What if I am a carer, friend or relative?

What support can I get?

If you are a carer, friend or family member of someone living with a dissociative disorder you can get support.

You can get peer support through carer support groups. You can search for local groups in your area on the following websites:

- Rethink Mental Illness: www.rethink.org

- Carers: Carers UK: www.carersuk.org

- Carers Trust: www.carers.org

If you need more practical support, you can ask your local authority for a carer’s assessment. You might be able to get support from your local authority.

As a carer you should be involved in decisions about your relative’s care planning. But you can only be involved if your relative agrees to this. If they don’t agree, their healthcare professionals can’t share information about them with you.

You can find out more information about:

- Carer’s assessment and support planning by clicking here.

- Confidentiality and information sharing – For carers, friends and relatives by clicking here.

- Benefits for carers by clicking here.

How can I supporting the person I care for?

You might find it easier to support someone with a dissociative disorder if you understand their symptoms, treatments and self-care options. You can use this to support and encourage them to get help and stay well.

You should also be aware of what you can do if you are worried about their mental state. Keep the details of their mental health team or GP handy and discuss a crisis plan with them.

You can find out more information about:

Further reading & Useful contacts

Caroline Spring

Online training on dissociation and Dissociative Identity Disorder, webinars and literature.

Website: www.carolynspring.com/

Clinic for Dissociative Studies

This organisation has lots of information on dissociative disorders on their website. They also provide care and treatment for dissociative disorders. They can accept referrals from the NHS. They offer general information about dissociative disorders but do not run a helpline.

Telephone: 020 7794 1655

Address: 35 Tottenham Lane, London, United Kingdom, N8 9BD

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.clinicds.co.uk

South London and Maudsley Trauma and Dissocation Service

A specialist outpatient assessment, consultation and treatment service. It’s for adults who are experiencing psychological difficulties following trauma and/or dissociative disorders. The only NHS specialist service offering treatment for people presenting with complex post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and severe dissociative disorders. Referrals are accepted from GPs and senior clinicians. All referrals have to be approved and funded by the local clinical commissioning group (CCG).

Phone: 020 3228 2969

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.slam.nhs.uk/national-services/adult-services/trauma-and-dissociation-service

Dissociative Experiences Scale

Source: Dissociative Experiences Scale

A Screening Test for Dissociative Identity Disorder

This 28-question self-test has been developed as a screening test for Dissociative Identity Disorder, formerly known as Multiple Personality Disorder.

Completing this Psychological Screening Test

This questionnaire consists of twenty-eight questions about experiences that you may have in your daily life and asks how often you have these experiences. It is important, however, that your answers show how often these experiences happen to you when you are not under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

To answer the questions, please determine to what degree the experience described in the question applies to you and choose the button which corresponds to the percentage of the time you have the experience. The left of the scale, labelled ‘Never’, corresponds to 0% of the time, while the right of the scale, labelled ‘Always’, corresponds to 100% of the time; the range covers 0% to 100% in 10% increments.

Take the Quiz

Please note: This test will only be scored correctly if you answer each one of the questions. Please also check our disclaimer on psychological testing and our psychological testing privacy guarantee.

Try Online Counseling: Get Personally Matched

About Scoring this Psychological Questionnaire

When your quiz is scored, one of two different information pages will appear to describe the results for scores in your range, along with further details of how your score was computed. Roughly speaking, the higher the score, the more likely a diagnosis of a dissociative disorder.

This screening test for Dissociative Identity Disorder is scored by totalling the percentage answered for each question (from 0% to 100%) and then dividing by 28: this yields a score in the range of 0 to 100.

Generally speaking, the higher the DES score, the more likely it is that the person has DID. In a sample of 1,051 clinical subjects, however, only 17% of those scoring above 30 on the DES actually had DID.

The DES is not a diagnostic instrument. It is a screening instrument. High scores on the DES do not prove that a person has a dissociative disorder; they only suggest that clinical assessment for dissociation is warranted. People experiencing DID do sometimes have low scores, so a low score does not rule out DID. In fact, given that in most studies the average DES score for a DID person is in the 40s, with a standard deviation of about 20, roughly 15% of clinically diagnosed DID patients score below 20 on the DES.

The figure shown below plots DES scores (horizontal scale) versus the number of subjects (vertical scale) from a sample of 1055 people. For further information about the DES, its validity and scoring, please visit the Ross Institute.

Distribution of DES Scores in the General Population.

Additional Information

Flash Technique: A Useful Tool

Edited by Sophie Linder

I first heard of the Flash Technique (“FT”) in my Eye Movement, Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy training by Dr. Philip Manfield in March 2019 in Oakland, California. EMDR is a form of psychotherapy that was developed by an American psychologist Francine Shapiro in the late 1980s. Since then, a lot of research has been conducted on the effectiveness of EMDR. Currently, EMDR is a widely recognized treatment for PTSD and other trauma-related conditions. The American Psychological Association (APA), among many others, lists EMDR as an evidence-based treatment for PTSD. EMDR consists of eight stages which typically require multiple psychotherapy sessions. During EMDR processing, the client focuses on the traumatic memory while eye movement, tapping, or another form of bilateral stimulation is used.

Dr. Manfield had developed FT in 2016, and was excited to share it with the class. Unlike EMDR, the Flash Technique does not require the client to commit to a lengthy process. It also does not require the client to focus on the traumatic memory for a long period of time. FT can be used as a part of EMDR treatment, or on its own. I thought that FT was an interesting tool, and I started using it along with the standard EMDR protocol. Sometimes I use FT to lower the intensity of the target, and then process the remainder by using traditional EMDR. My practice was both online and in person, and I used FT with both virtual and in-office clients. My interest in FT grew over time as I was getting good results, and I took the Flash Technique webinar in May 2020. In December 2020, I took the Advanced Flash Technique webinar. As of this writing, I have used FT with dozens of clients in the last two years. I have found it easy to use and very effective when working on a variety of disturbing memories and fears. It usually takes about 15 minutes to implement FT, making it very easy to fit into the standard 50 minute session.

The Flash Technique process starts with identifying a memory or fear, and ranking the level of disturbance that the client feels in that moment. The scale is 0–10, with 10 being the most disturbing. Next I ask the client to think of something fun or exciting that they can talk about for the next 10–15 minutes (i.e., a hobby, a pet, a movie, a trip). This is referred to as the Positive Engaging Focus (PEF). Then I demonstrate for the client how to cross their arms on their chest and tap on the arms (a butterfly hug). While they are tapping and talking about the PEF, I periodically ask them to blink several times in rapid succession. After five or so sets of blinks, I ask them to pause and touch on the target memory/fear. They rank the disturbance and tell me what they notice about the memory. Usually the target is less vivid and harder to pull up. Then we continue with the PEF and more blinking and tapping. Next we pull up the target again. This process continues until the target is no longer disturbing.

In the following session, usually a week later, I recheck the target memory or fear to see if there is still any disturbance. Some targets resolve in one session and the results hold over time. Typically, the easiest cases are single-incident traumas — an event that took place at one time and does not have any related memories. For example, someone who was in a car accident once and developed a fear of driving can usually process the incident in one session without any need for additional work. In other cases, usually when there are many related memories, it requires additional sessions of Flash or EMDR to fully resolve them. Multiple incidents can also be processed but may require additional sessions.

I should note that Flash, like EMDR, does not completely remove all fear. I would not want my clients to put themselves in unsafe situations following FT. Rather, FT and EMDR aim to take away the extreme disturbance associated with a traumatic event. The client still remembers that the event took place, and experiences a normal level of anxiety in appropriate situations. FT does not offer any superpowers or magical thinking. It removes the irrational fear so that the client can comfortably engage in everyday activities.

Here are several case examples in which I used FT:

Abbreviations:

FT = Flash Technique

SUDS = subjective units of distress (scale is 0–10, with 10 being most disturbing)

PEF = positive engaging focus (something positive and exciting that the client talks about during the sets)

Mugging

Della, a 33-year-old Caucasian female, was mugged seven years ago on the street. Since then, she had been unable to walk alone at night. She always had to have someone walk her places after it got dark, or she avoided going out altogether. She stated, “I want to be able to walk alone at night if I need to.” Della lived in a safe suburb and did not have an urgent need to go anywhere at night. More recently, Della’s company offered to relocate her to Paris. Della was excited about the opportunity, but realized that she needed to work on this fear if she was going to move to a big city.

We discussed the mugging in more detail. The incident happened when she was in college. She was studying late at the library, and drove home to her apartment at around 2 a.m. She parked her car in a garage a block away from her apartment. As she was walking home, three people came up behind her. They kicked her to the ground, grabbed her backpack containing a laptop, and drove away. When asked to rank the disturbance associated with this memory, Della stated it was a 9 on the 0–10 scale. For Flash, we chose Paris as her positive engaging focus. “I’m excited to move there,” Della said. After five sets of Flash which took about 10 minutes, Della ranked the disturbance at 1 before the session ended.

Two weeks later, Della reported that she had chosen a safe area in her suburb as a test for an evening walk. She walked alone at around 8 p.m. Della stated, “This is something I haven’t been able to do since the mugging seven years ago.” She said that it felt good to walk around and look at the lights. In the past, she would have felt very anxious at the thought of walking alone at night. “This time, I didn’t have any physical symptoms,” said Della. She described that she did feel a little nervous, ranking the SUDS at 1–2. However, it felt like a normal amount of anxiety compared to the paralyzing fear she had experienced previously. She felt good about the outcome. “I wanted to be able to walk alone at night if I had to, and now I can do that,” Della remarked.

Fear of being alone

Danielle, a 37-year-old mixed race Caucasian and Asian-American woman, sought therapy with me for anxiety and depression in July 2020. Danielle shared that her “number one fear” was of being alone, and one day, dying alone. Danielle ranked the SUD at a 10. One of the contributing factors to this fear was Danielle’s current relationship with her boyfriend of a couple years. Danielle wanted to move in together, but her boyfriend decided that he wasn’t ready, and instead rented a one-bedroom apartment in another city. Danielle stayed in her one-bedroom apartment where she was living by herself. In addition, her best friend had moved away recently. “I am afraid I will always live alone in an apartment.” The fear was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting isolation.

To me, the fear seemed largely irrational as Danielle was a very attractive woman with an impressive educational background and a successful career. She had a great personality, was easy to talk to, and had interesting thoughts and ideas. We decided to use Flash on this fear, and we used food as the PEF. After two sets, SUD decreased from 10 to 7–8. When I asked Danielle what was different about the target, she stated, “I’m not in the visual anymore.” After two more sets, Danielle reported, “I feel less sad.” SUD = 6.

A few weeks later, we checked on her fear of being alone. Danielle ranked the disturbance at 3–4. I asked her to explain the source of her disturbance. Danielle replied, “My grandma died alone in a nursing home. She was a prom queen in high school–I have a picture of her. By the time she died, she was decrepit and had bad teeth. I feel guilty that I didn’t visit her.” We decided to continue with Flash. For PEF, Danielle chose comics and graphic novels. After two sets, she reported that the image had faded. “I feel guilty we weren’t close,” she said. Danielle cried and reported the disturbance at 6–7. She pointed out that the fear of being alone on its own was at 2. After the third set, she stated, “The strong emotions about my grandma have dissipated,” and was no longer crying. After the fourth set, she reported, “I feel less afraid of the memory.” For grandma, SUD = 1; for the fear, SUD = 0. She added, “There are things I can do in my lifetime.” I guided Danielle in instilling this positive belief using slow self-tapping. By the end of the session, Danielle was smiling.

The following week, I asked Danielle about the fear of being alone. She stated, “I used to think about it throughout the day, every day, but now I don’t think about it.” She said it felt like 0–1 now. Danielle added, “I am more focused on what I can do now to create a better future for myself.” She reported that she started to organize her finances this past week. She also engaged with new and old friends with the goal of having deeper friendships. I asked Danielle what she thought of the Flash technique, and she said she found it helpful.

Dad’s Addiction Issues

Claudia, a 31-year-old African-American female sought therapy with me in January 2021 to work through family issues. Claudia achieved a lot in her life; she put herself through undergraduate and graduate school where she studied biochemistry, and landed her dream job where she was succeeding. She was happily married to a wonderful young man. However, she struggled with anxiety, especially around her father’s past and current substance abuse issues. Claudia explained that her father was an active alcoholic and has abused cocaine on occasion since she was a child. I asked her to write down her 10 worst memories. Six of her 10 memories involved her father. We noted how disturbing they felt as we went over them.

In our next session, we targeted the first bad memory which was “Dad being high at dinner.” Claudia was 14 at the time. She rated the disturbance associated with the memory (SUD) at 6. Claudia picked her honeymoon as her PEF. With each set of Flash, the disturbance associated with the memory went down by 0.5–1. After eight sets, Claudia reported that the memory did not bother her anymore. “I can’t see my dad’s face anymore,” she said. In the following session, we checked the memory and the disturbance was back at 3. For her PEF this time, Claudia chose her wedding. After two sets, she reported that the event was “hard to recall.” The memory no longer had a hold on her. “I feel indifferent,” she said. The positive belief was “I’m not at fault.” I asked Claudia to close her eyes and play the event in her mind while repeating the words “I am not at fault” as she tapped slowly.

Next I asked Claudia to imagine a folder named “Dad’s addiction issues.” I asked her how disturbing it felt to think of the folder, and Claudia said 5–6. For her PEF, Claudia decided to continue talking about her wedding. After two sets of Flash, she reported that, “Specific memories are hard to pull up.” After two more sets, she reported there was no disturbance. We checked each Dad-related memory, and the disturbance was 0–1 for each. In our next session, I asked about the memory of dad being high at dinner. Claudia reported that she felt 0 disturbance. I asked if there was anything else that felt disturbing to her regarding her dad’s addiction. She replied, “Yes, I am worried about his health. He continues to drink, and he could have a stroke and die early.” This fear felt like a 2 to her.

I decided to use the standard EMDR protocol for this fear. The negative belief was “I’m not in control”; the positive belief was “I can handle whatever happens.” We worked through several channels. One aspect that was particularly painful for Claudia was that her brother was very close to their dad. She cried when she thought about the pain her brother would feel if her father had a stroke in the near future. I used several cognitive interweaves which Claudia found helpful: “You’ve done your part,” and “We don’t know when your dad will pass; he could live for a long time despite his addiction issues.” After several sets, Claudia realized that she would be there for her brother when her dad passes away, which she found to be calming.

By the end of the session, the fear of her father’s early death was no longer impacting her. “If it happens, I can handle it,” Claudia stated. We conducted a body scan which revealed that the pit in her stomach from earlier in the session went away. Claudia reported that she felt good about the work we had done, and at peace regarding her father’s addiction. She no longer felt that it was her fault, or that she should be doing something to force him to stop (which she had tried in the past without success). She felt free to enjoy her relationship with her father as it is today, and let go of fear of the future.

Fear of Cats

Georgia, a professional Hispanic woman in her late 20s, had an extreme fear of cats which made her life difficult. She couldn’t visit her best friend, Zoe, because Zoe had a cat at home. When Georgia saw cats on the street, she felt apprehensive and had to walk away immediately. Georgia was single and actively dating, but had to exclude any potential partners who lived with a cat.

It turned out that Georgia had a traumatic experience with cats as a child. She explained, “It was during my first piano exam at my instructor’s house. I was nervously waiting for my turn to play, and four cats came up to me and scared me.” The cats appeared suddenly and came up to her from behind. Georgia estimated her age to be seven years old at the time. When I asked her how disturbing this memory felt now, she ranked it a 6 on the 0–10 scale. We decided to process this memory with the Flash Technique. We used Georgia’s favorite TV dating show as a PEF. After two sets, Georgia remembered that during a sleepover in high school, a cat jumped on her bed which was scary. After one more set, the fear was 0. This process took about 10 minutes.

In our next session a week later, Georgia reported that the memory of the four cats at the piano exam was not disturbing (SUD=0). I asked Georgia to imagine visiting Zoe and her cat. She reported there was no disturbance. I asked Georgia to pull up a picture of a cat online, and she reported 0 disturbance. Then I asked her to search for a video on YouTube of a cat attacking a person. She watched the video in session and her facial expression was unremarkable; again there was no disturbance. After a few weeks, Georgia reported that the piano exam memory did not produce any disturbance. Picturing cats was not disturbing. Due to the COVID-19 quarantine, she had not had a chance to visit any friends with cats yet.

After a few more weeks, Georgia reported that the fear of cats was 0. She added, “There are some cats that walk on the fence in my backyard. I used to find it really irritating and distracting. I would try to scare them off. Every other weekend I would spray the fence with vinegar to keep them away. It didn’t work! They still came back. Now it doesn’t bother me. The other day I even thought the cat was cute.” Georgia explained that she did not fall in love with cats or anything like that, but the fear was no longer there. She felt neutral towards them which allowed her to live her life with more peace. This result was well worth the 10 minutes that she spent trying out the Flash technique.

Aside from the above examples, I have successfully used FT with other clients, focusing on a variety of negative memories and fears. Some examples include a parent’s suicide, childhood bullying, extreme fear of bugs, chronic pain and fear of becoming disabled, fear of contracting COVID-19, sexual assult, car accident/fear of driving, near drowning/fear of swimming. In some cases, the problem resolved after 15 minutes of FT with no resurgence. In other cases, FT provided some benefit but additional EMDR work was required to fully re-process the event and maintain results over time. To date, I haven’t had any negative experiences with FT. Most clients have found FT to be helpful and enjoyable.

It should be noted that FT, like any other therapeutic intervention, may not be effective for every client or issue. Clients should be aware of potential risks and limitations of FT before starting therapeutic treatment.

About the author: Annia Raysberg, MFT is a therapist in private practice living in Castro Valley, CA. She is currently working with clients via video. For more information, please visit AnniaRaysberg.com.

Client’s names and other identifying details have been changed. Written permission has been received from clients.

Articles on Flash:

Manfield, P., Lovett, J., Engel, L., & Manfield, D. (2017). Use of the flash technique in EMDR therapy: Four case examples. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 11(4), 195–205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.11.4.195.

EMDR and The Flash Technique: A match made in heaven? — EMDR Therapy Quarterly (emdrassociation.org.uk)

Shebini, N. (2019). Flash technique for safe desensitization of memories and fusion of parts in DID: Modifications and resourcing strategies. Oct 2019, Frontiers of the psychotherapy of trauma and dissociation Vol 3 3(2):151–164 2019 ISSN 2523–5117 print/ 2523–5125 online

Wong, Sik-Lam. (2019). Flash technique group protocol for highly dissociative clients in a homeless shelter: A clinical report. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 13(1), 20–31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.13.1.20

About EMDR Therapy

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy is an extensively researched, effective psychotherapy method proven to help people recover from trauma and other distressing life experiences, including PTSD, anxiety, depression, and panic disorders.

The American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the U.S. Dept. of Veterans Affairs/Dept. of Defense, The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and the World Health Organization among many other national and international organizations recognize EMDR therapy as an effective treatment. More specific information on treatment guidelines can be found on our EMDR and PTSD page.

How is EMDR therapy different from other therapies?

EMDR therapy does not require talking in detail about the distressing issue or

completing homework between sessions. EMDR therapy, rather than focusing on changing the

emotions, thoughts, or behaviors resulting from the distressing issue, allows the brain to

resume its natural healing process.

EMDR therapy is designed to resolve unprocessed traumatic memories in the brain. For

many clients, EMDR therapy can be completed in fewer sessions than other

psychotherapies.

How does EMDR therapy affect the brain?

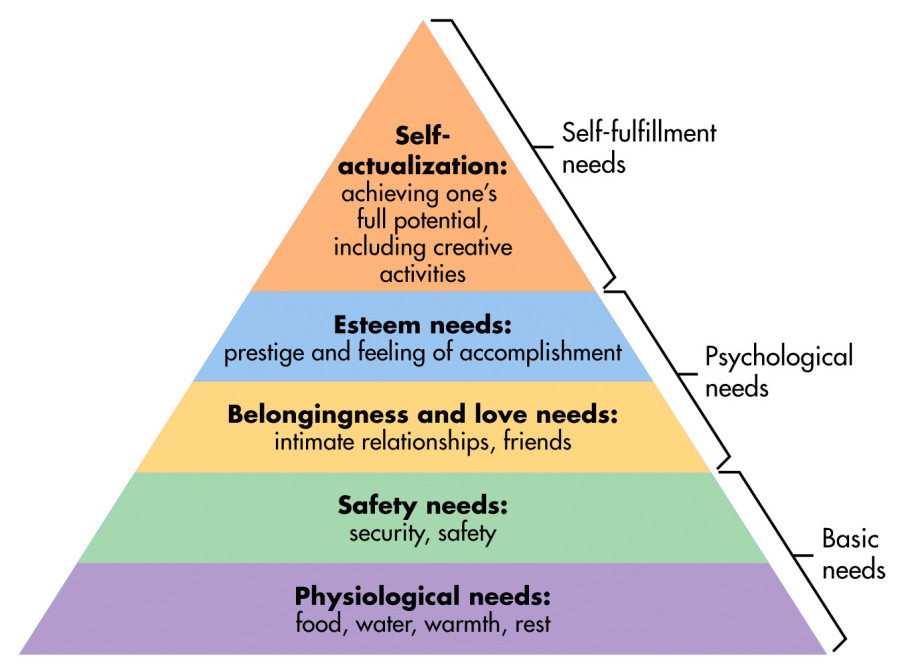

Our brains have a natural way to recover from traumatic memories and events. This process involves communication between the amygdala (the alarm signal for stressful events), the hippocampus (which assists with learning, including memories about safety and danger), and the prefrontal cortex (which analyzes and controls behavior and emotion). While many times traumatic experiences can be managed and resolved spontaneously, they may not be processed without help.

Stress responses are part of our natural fight, flight, or freeze instincts. When distress from a disturbing event remains, the upsetting images, thoughts, and emotions may create feelings of overwhelm, of being back in that moment, or of being “frozen in time.” EMDR therapy helps the brain process these memories, and allows normal healing to resume. The experience is still remembered, but the fight, flight, or freeze response from the original event is resolved.

Who can benefit from EMDR therapy?

EMDR therapy helps children and adults of all ages. Therapists use EMDR therapy to address a wide range of challenges:

- Anxiety, panic attacks, and phobias

- Chronic Illness and medical issues

- Depression and bipolar disorders

- Dissociative disorders

- Eating disorders

- Grief and loss

- Pain

- Performance anxiety

- Personality disorders

- PTSD and other trauma and stress-related issues

- Sexual assault

- Sleep disturbance

- Substance abuse and addiction

- Violence and abuse

Can EMDR therapy be done without a trained EMDR therapist?

EMDR therapy is a mental health intervention. As such, it should only be offered by properly trained and licensed mental health clinicians. EMDRIA does not condone or support indiscriminate uses of EMDR therapy such as “do-it-yourself” virtual therapy.

EMDR Therapy is a Recognized Effective Treatment for PTSD

Anyone can experience intense trauma. EMDR therapy is widely considered one of the best treatments for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and it has been endorsed as an effective therapy by many organizations.

Complex PTSD Symptoms And Treatment | Betterhelp

Source: Complex PTSD Symptoms And Treatment | Betterhelp

By: Darby Faubion

Updated January 08, 2021

Medically Reviewed By: Melinda Santa

If you or someone you love is currentlyaffected by Complex PTSD, it can feel like you don’t know what else to do. You might feel stuck or alone in your struggle. No matter what you’re experiencing right now or in the past, there are tools to help you move forward to a life that feels lighter, happier, and healthier. The fact that you’re here right now looking for answer is a great indicator that hope is not lost. Taking the courageous step to investigate and pursue treatment for managing your symptoms is a victory.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a trauma-based mental illness. It manifests in many ways and can look very different. Often it causes severe anxiety around certain triggers, a sense of jumpiness, distressing nightmares, and persistent feelings and symptoms of distress. Anyone who has experienced, witnessed or repeatedly been exposed to details of atraumatic event may develop PTSD in response. In particular, individuals who have experienced repeated or ongoing trauma may be at risk for developing Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD).

While PTSD may develop after a single incident, C-PTSD is a group of complex symptoms that result from long-term traumatic events. Examples of ongoing trauma include long-term physical or sexual abuse, ongoing domestic violence, being a prisoner of war, or being a victim of commercial sexual abuse, including trafficking or prostitution. C-PTSD is thought to be more severe in those who experienced traumatic events for a long time, at a young age, were alone in the experience, or the experience was enacted by a caregiver, especially one they are still in contact with.

In this article, we’ll look closer at the symptoms, which bear similarity to the symptoms of PTSD, and treatment for Complex PTSD.

This website is owned and operated by BetterHelp, who receives all fees associated with the platform.

Source: unsplash.com

Symptoms of C-PTSD

Complex Post-traumatic Stress Disorder usually encompasses the following PTSD symptoms:

- Avoidance

- Avoiding places, people, or situations that remind someone of the traumatizing event(s)

- Avoiding thoughts, memories, and feelings of the traumatizing event(s)

- Re-experiencing

- Nightmares of the traumatizing event(s)

- Distressing flashbacks of the traumatizing events(s)

- Frightening thoughts about the traumatizing event

- Mood and Cognition

- Distorted or misplaced thoughts of guilt or blame

- Negative thoughts about the world or oneself, including a sense of hopelessness or worthlessness.

- Loss of interest in hobbies and activities

- Problems remembering specific events relating to or surrounding the period of trauma

- Arousal and Reactivity

- Sleeping problems, including waking early, insomnia, and oversleeping

- Feeling stressed, on edge, or irritable

- Feeling jumpy or startlingeasily

- Experiencing outbursts of anger

Source: pexels.com

In addition to the list above, people suffering from C-PTSD may also experience the following symptoms:

- Difficulty relating to others

- An ongoing search for a rescuer

- Distrust of others

- Isolating oneself from relationships, even close ones

- Avoiding close relationships altogether

- Difficulty regulating emotions

- Outbursts of anger

- Persistent sadness and depression

- Suicidal thoughts. If you are experiencing thoughts of suicide, reach out for help immediately. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can be reached at 1-800-273-8255.

- Cognitive difficulties

- Problems with memory (forgetting traumatic events or details surrounding them)

- Feeling disassociated or detached from emotions and their sense of self

- Reliving traumatic events persistently

- Difficulty with self-perception

- Perceiving oneself as guilty and unworthy of help

- An overwhelming sense of shame

- Perceiving themselves as helpless

- Feeling different from others

- Preoccupation with the perpetrator/perpetrators

- Preoccupation with revenge

- Preoccupation with one’s relationship to the perpetrator

- Attributing power to the perpetrator

- Damage to one’s belief system

- Lack of faith

- Inability to feel hopeful

- Overwhelming feelings of despair

Because children and teenagers do not have the same coping mechanisms as adults, the symptoms they exhibit after prolonged traumatic events may be a little bit different. For example, children who are six years old or younger may also experience the following symptoms:

- Bedwetting after they have learned to use the toilet

- Acting out the traumatic event while playing

- Loss of speech

- Clinging to a parent or other adult; fear of being separated from them

Older children and teens experience many of the same symptoms as adults, although sometimes also experience the following symptoms of C-PTSD:

- Disrespectful or destructive behavior

- Misplaced guilt over not being able to prevent death or injury

- Feelings of or a preoccupation with revenge

Standard behavioral therapies teach coping mechanisms and help individuals to recognize and change their negative thoughts and behaviors. This type of therapy also focuses on addressing symptoms as they arise, rather than ignoring them or trying to push through them to something more positive.

At times, it may be necessary or helpful to use medications to manage C-PTSD symptoms. Some medication regimens may include antidepressants, anti-anxiety medications, and sleep aids.

Antidepressants help to relieve some negative mood symptoms, such as excessive guilt, shame, and blame. Alternatively, anti-anxiety medications are used to help relieve the symptoms of fear, worry, and stress that often accompany a diagnosis of C-PTSD.

Another therapeutic method known as cognitive restructuring therapy focuses on dealing with how the traumatic event occurred and helping the patient understand theirthought processes around the event. For many, self-blame, guilt, and shame are major symptoms of the diagnosis, so restructuring therapy helps put traumatic events in perspective. It works to ease these feelings by looking at the reality of the situation.

Source: pexels.com

Exposure therapy is a type of psychotherapy that exposes individuals to the trauma they once experienced in a safe way. During exposure therapy, individuals learn to face their fears, recognize their own ability to cope with it, and exert control over their reactions and impulses. This therapy often works for people who have severe symptoms of anxiety related to their traumatic experiences. It may be a step taken later on in a patient’s treatment plan.

There Is Help

The fear of rejection that often accompanies a C-PTSD diagnosis may cause some people to be apprehensive about seeking help. The benefits of talking with someone who can help you navigate the healing process is crucial.

There are many options for talking with a counselor or therapist. Some people prefer to meet in-person in a controlled setting, like a therapist’s office. It provides a safe place to explore feelings and learn new tools. Others may prefer to have more control over when and where they communicate with a counselor. In these instances, online counseling is a great option.

BetterHelp,an online counseling platform, can connect you with experienced counselors, doctors, and social workers who can help you address Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and any other mental health issues you may be facing. Their goal is to provide professional help to anyone who needs assistance navigating life’s difficulties.Online counseling for battling symptoms related to C-PTSD, like depression and anxiety, has been shown to be just as effective as in-person sessions. A study looking at 318 BetterHelp users found that those users experienced a significant reduction in depressive symptoms in just 3 months of sessions.

Online counseling can be a great, straight forward to begin receiving help today. With no waiting around for an open spot in your local counselor’s office, online counseling can begin as soon as you’re ready, whether via messaging or phone calls or video chats. Plus, BetterHelp’s service is completely confidential, making sure your information stays safe and private.

Below you’ll find some reviews of BetterHelp counselors from people experiencing similar issues.

Counselor Reviews

“Ted is an example of what a person is gifted to do!!! Has given me direction to go forward with complex PTSD. It’s been a productive year and looking to more growth.”

“Dr. Cooley was able to identify my needs and address appropriate therapy. I no longer have PTSD events that are not manageable. He has given me tools and resources to deal with my issues. I became brave enough to make positive change in my life and found I could experience joy and genuine love.”

Conclusion

Dealing with any kind of trauma can feel overwhelming, but help is available. If you’re affected by complex post-traumatic stress disorder, you can learn tools to work through your trauma and regain your sense of power and identity. With help from a qualified therapist, it’s possible to gaincoping mechanisms to lead a healthier life. Take the first step today.

Previous Article

Do You Suffer From Survivor’s Guilt?

Next Article

Common Treatments For PTSD Nightmares

How EMDR Helped Me Find Healing in a Most Daunting Year

In 1987, psychologist Francine Shapiro, Ph.D., noticed that moving her eyes from side to side while contemplating difficult thoughts improved her mood. Intrigued, she went on to research and develop EMDR. Shapiro suggests there are approximately 10 or 20 unprocessed memories responsible for most of the pain in our lives. The efficacy of EMDR therapy in the treatment of PTSD has since been well established, as evidenced by the results of over 30 positive randomized controlled studies over the past three decades. Such findings led the World Health Organization to state in 2013 that Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) and EMDR are the only psychotherapy modalities recommended in the treatment of those diagnosed with PTSD.